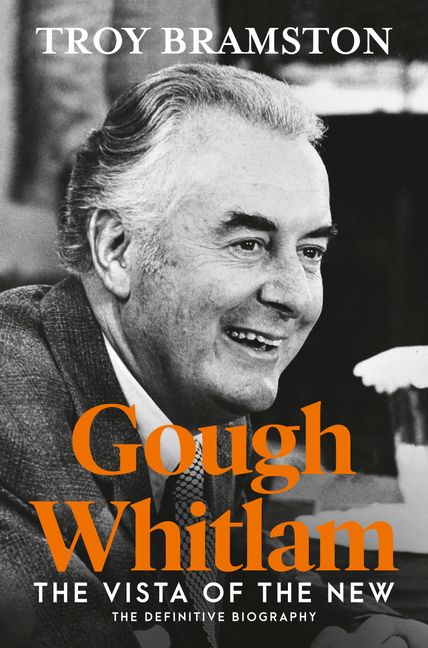

Gough Whitlam: The vista of the new by Troy Bramston

Troy Bramston is fast becoming the Peter FitzSimons of Australian political biography. Every few years a door-stopping volume on a prime minister appears, brandishing the same formula of ‘never before seen’ documents and ‘fresh revelations’. In the Acknowledgements to this latest biography of Gough Whitlam, Bramston virtually pleads with readers to render homage to the ‘hundreds’ of interviews he conducted, the ‘thousands’ of pages turned in archives, the miles clocked in libraries visited. There is a diligent busyness to the enterprise. But Bramston’s relentless emphasis on the quantitative smothers his underlying inability to master the material. The result, sadly, is an incomplete picture of Whitlam: a workman-like chronicle of the life, but not a deep exploration of the political and intellectual dimensions of the man.