Clinton Fernandes

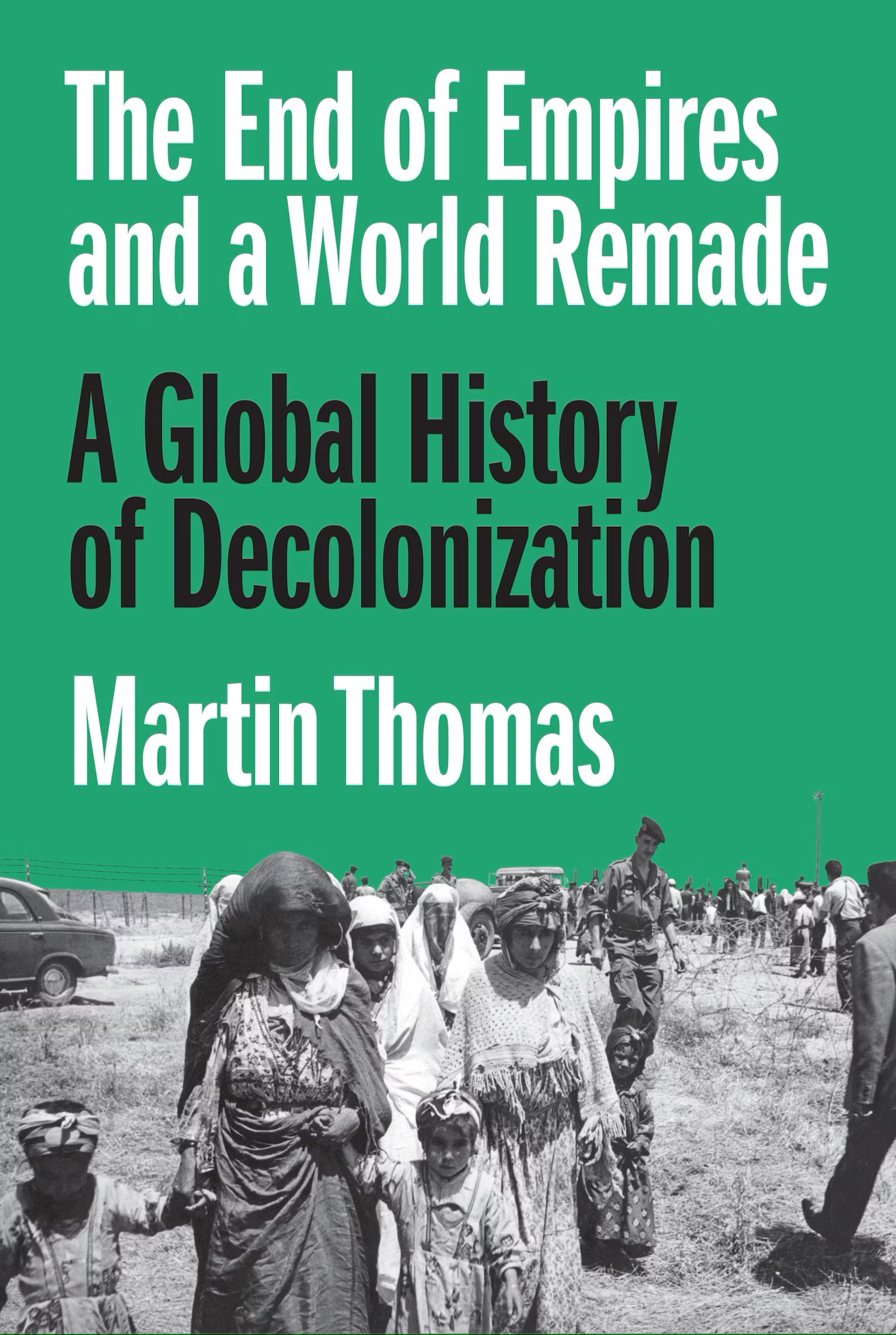

The End of Empires and a World Remade: A global history of decolonization by Martin Thomas

Twenty-five years ago, an international peacekeeping force entered East Timor, delivered it from Indonesian occupation, and placed it under United Nations administration. Known as the International Force East Timor (InterFET), it had 11,000 troops from twenty-three countries and was commanded by an Australian major general. Everything about these events seemed miraculous. East Timor’s independence had long been regarded as impossible; a top adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt observed during World War II that it might eventually achieve self-government, but ‘it would certainly take a thousand years’. Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975 while the latter was in the process of decolonising from Portugal, annexed it the following year, and declared its rule ‘irreversible’.

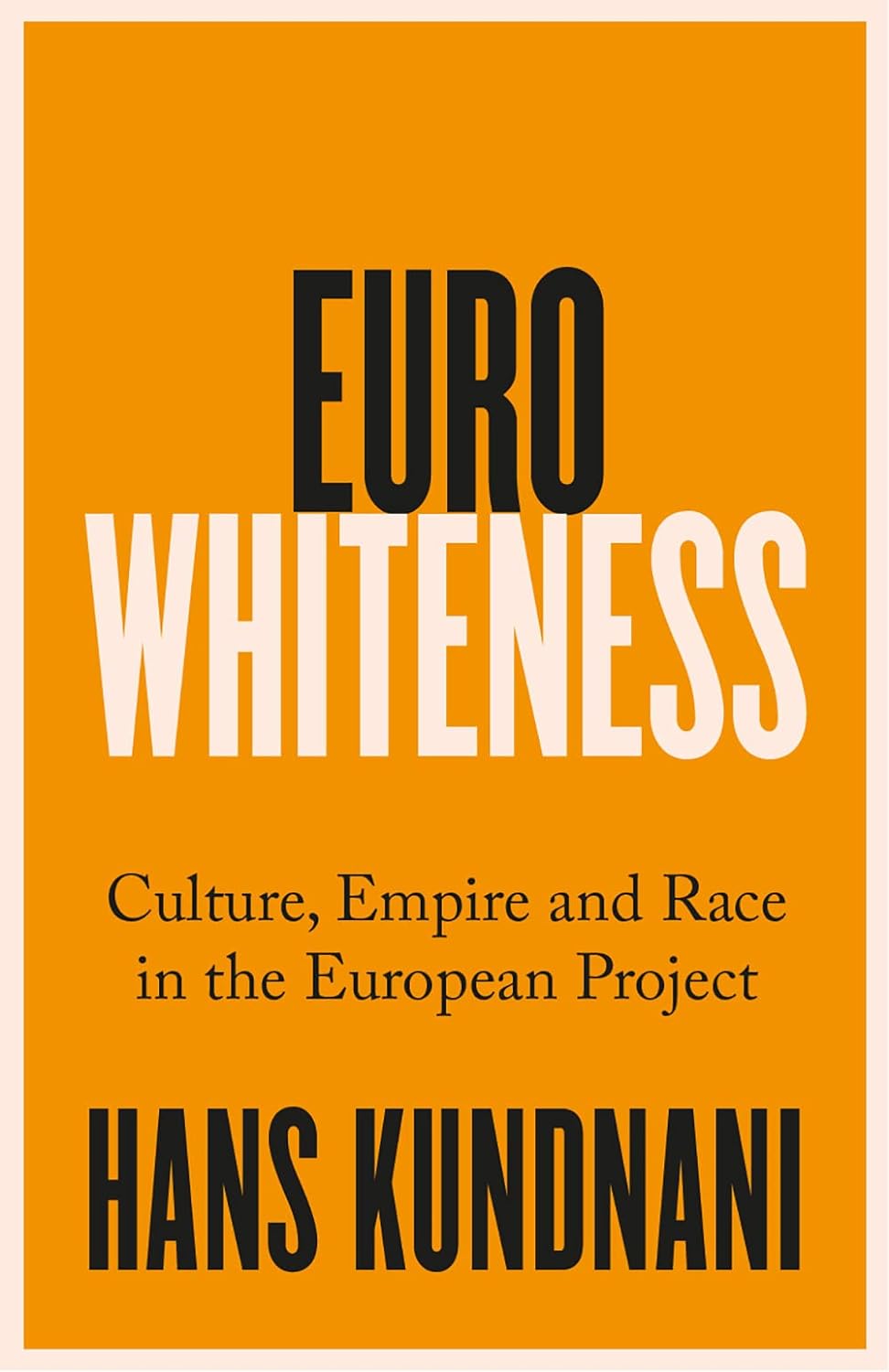

... (read more)Eurowhiteness: Culture, empire and race in the European project by Hans Kundnani

Empire, Incorporated: The corporations that built British colonialism by Philip J. Stern

Unlike in the United States and several other Western nations, Australian governments are under no compulsion to consult parliament before sending troops to war. In Subimperial Power: Australian in the international arena, Clinton Fernandes argues that this reflects, and furthers, Australia’s longstanding ambition in foreign affairs, which is to demonstrate its usefulness to the United States. In this week’s ABR Podcast, Kevin Foster, an academic at Monash University who has published widely on war in the Australian media, reviews Subimperial Power.

... (read more)