Accessibility Tools

- Content scaling 100%

- Font size 100%

- Line height 100%

- Letter spacing 100%

Archive

The ABR Podcast

Released every Thursday, the ABR podcast features our finest reviews, poetry, fiction, interviews, and commentary.

Subscribe via iTunes, Stitcher, Google, or Spotify, or search for ‘The ABR Podcast’ on your favourite podcast app.

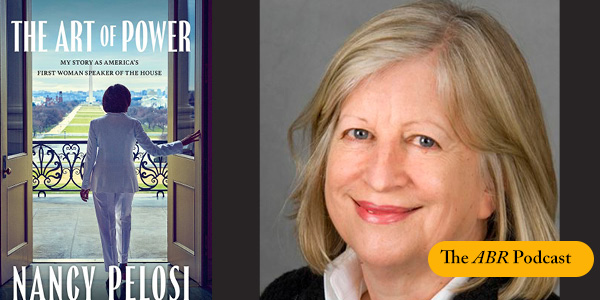

‘Where is Nancy?’ Paradoxes in the pursuit of freedom

by Marilyn Lake

This week on The ABR Podcast, Marilyn Lake reviews The Art of Power: My story as America’s first woman Speaker of the House by Nancy Pelosi. The Art of Power, explains Lake, tells how Pelosi, ‘a mother of five and a housewife from California’, became the first woman Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. Marilyn Lake is a Professorial Fellow at the University of Melbourne. Listen to Marilyn Lake’s ‘Where is Nancy?’ Paradoxes in the pursuit of freedom’, published in the November issue of ABR.

Recent episodes:

War Criminals Welcome: Australia, a Sanctuary for fugitive war criminals since 1945 by Mark Aarons

The judges for this prestigious award are Bernard Smith, Mary Lord, Graham Rowlands and Rick Hosking. Some proven stayers, good mud gallopers, smart on top of the ground, they are judges amply qualified to assess a varied field.

We offer a form guide provided by well-known Sydney racing identity, Don Scott.

... (read more)The Poetry of Judith Wright:: A search for unity by Shirley Walker

More than thirty years after the last helicopters left the roof of the American embassy in Saigon, the flow of new books on the Vietnam war shows no sign of abating. Among them are some intended for a limited, scholarly market, some for a wider general readership; some for Americans, some for Australians. These three books exemplify some of the trends in both the substance and the style of Vietnam war histories, and illustrate both the virtues and the faults of differing approaches to the most controversial conflict of the twentieth century.

... (read more)In November 1984 when I left Queensland to come back to Victoria, Kathy de Bono, a friend from the Yoga school, followed me to Murwillumbah where I was catching the train. She told me that because my car was old she’d drive slowly behind me in case I broke down. Now my Lesley McGinley doesn’t look much, but it goes like the clappers. Out of mischief I flattened my foot when I’d crossed the Tweed, and Kathy soon became a speck in my rear vision mirror. When she reached Murwillumbah she said ‘I brought a packet of tissues in case you cried. Instead you’re all lit up and laughing.’

... (read more)Writing fiction is something I originally stumbled upon rather than consciously chose. Much the same can be said of my career as student and university teacher. Brought up in London in a lower working-class family, I certainly harboured no intellectual or literary ambitions. Like the rest of my family, I looked forward only to escaping from school as soon as possible and settling down to a steady job. What challenged that way of thinking was my parents’ unexpected decision to go to Northern Rhodesia (as it was then) when I was fifteen. Central Africa, where I was to spend a good portion of the next twenty years, did more to alter my attitudes and prospects than anything before or since. Still under British rule, it showed me the last and perhaps the ugliest face of colonialism; and in so doing destroyed any smug sense I may have had of my own Englishness. Equally, the politics of an emerging Zambia taught me some painful and abrupt lessons about both myself and the twentieth century preoccupation with violence.

... (read more)As the child of survivors of a war-battered, sorely depleted driftwood generation, I have acquired reasons in plenty to call myself lucky. Perhaps more, far more, than merely lucky.

... (read more)