Archive

Jake Wilson reviews ‘The Year’s Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 2004, Volume One’ edited by Bill Congreve and Michelle Marquardt and ‘A Tour Guide in Utopia: Stories by Lucy Sussex’ by Lucy Sussex

The useful introduction to The Best Australian Science Fiction and Fantasy 2004 (the first volume in an intended new series) gives an idea of the less than adequate state of genre publishing in Australia. For the moment, it seems that science fiction (SF) authors in particular are mainly confined to semi-professional magazines and small presses, or are obliged to seek international markets for their work. Though the editors understandably do not say so, the fact of a small pond necessarily produces some relaxation of expectations. There is much amateurish writing in this collection, and a more serious lack of urgency: many contributors seem less interested in creating new myths than amusing themselves with borrowed ones, like fans dressing up for a convention.

... (read more)John Carmody reviews ‘The Beginner’s Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize: A life in science’ by Peter Doherty

We revere Nobel laureates – and rightly. Sometimes that admiration is not repaid well, and those eminences become prey to a variant of Lord Acton’s wisdom – ‘All fame tends to corrupt’ – and consider themselves intellectual Pooh-Bahs: ‘Lord High Everything Else.’ A consequential risk of such renown is that bystanders who can see and vouch for reality are commonly unable to tell the truth to the famous.

... (read more)John Thompson reviews ‘T.W. Edgeworth David: A life’ by David Branagan

With the publication of Eminent Victorians in 1918, Lytton Strachey famously created a new mode of biographical writing – spare, ironic, satiric, detached. In his preface to that slim cathartic volume of portraits of four famous Victorian personalities, Strachey extolled the biographer’s virtue of what he called ‘a becoming brevity’. That preface has been called a ‘manifesto of modern biography’. In his breaking of new ground, Strachey turned his back on the sombre and dutiful ‘lives’ that had become the accepted mode of biographical homage in Victorian England.

... (read more)Jonathan Pearlman reviews ‘Men And Women of Australia!’: Our greatest modern speeches’ edited by Michael Fullilove

There was no chaplain aboard the troopship Transylvania as it travelled across the Mediterranean Sea for France in 1916, so the sermon was left to Frank Bethune, a Tasmanian clergyman and private soldier. Bethune rose on the promenade deck and informed the soldiers that, god-fearing or not, they were righting a great wrong and were not heroes, but men. ‘What else do we wish except to go straight forward at the enemy?’ he asked. ‘With our dear ones far behind us and God above us, and our friends on each side of us and only the enemy in front of us – what more do we wish than that?’ Also aboard the ship was Australia’s official war correspondent, Charles Bean. After describing the effect of Bethune’s sermon on the soldiers, Bean delivered the ultimate praise: ‘[There] were tears in many men’s eyes when he finished – and that does not often happen with Australians … And that was because he had put his finger, just for one moment, straight on to the heart of the nation.’

... (read more)Kate McFadyen reviews ‘The Grasshopper Shoe’ by Carolyn Leach-Paholski and ‘A New Map of the Universe’ by Annabel Smith

Early in Carolyn Leach-Paholski’s The Grasshopper Shoe, a maverick artisan named Wei argues that ‘all form strives to the enclosed and therefore piques our curiosity. What lies open or does not have a hidden side could be counted as formless. All that remains unjoined, the line which does not seek the satisfaction of unity in the circle, all this to aesthetics is dead.’ These words could be interpreted as the novel’s declaration of formal intent. Indeed, both of these début novels are concerned with beauty and perfection, in the sense that they seek to convey emotional and philosophical intensity through rich poetic language. The use of ornate metaphors and imagery in prose has its risks. It requires skill and a good deal of restraint to allow the narrative enough air to breathe so that the novel’s momentum is not stifled.

... (read more)Nicholas Jose’s new novel, Original Face, begins violently. On the first page, a man is – expertly, and with a small knife – skinned alive, his face removed. We are in Sydney and the assassin’s name is Daozi, which in Chinese means knife. Jose’s seventh work of fiction traces the sometimes-brittle nature of identity as it plays with an ancient Chinese riddle: ‘Before your father and mother were born, what was your original face?’ It’s a confidently crafted pastiche; a kind of film-noir literature with a tender twist of Buddhist philosophy.

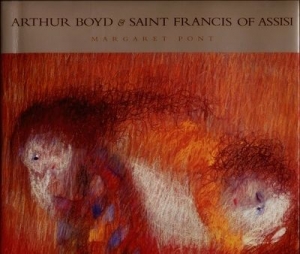

... (read more)Luke Morgan reviews ‘Arthur Boyd and Saint Francis of Assisi: Pastels, lithographs and tapestries, 1964–1974’ by Margaret Pont

Arthur Boyd and Saint Francis of Assisi is based on Margaret Pont’s Master’s thesis, which she wrote at the University of Melbourne under the supervision of the medievalist Margaret Manion. During the 1960s, Arthur Boyd made more than twenty pastels depicting various events from the saint’s life. He followed this with a series of lithographs, all of which are listed in Pont’s detailed catalogue. Then, from 1972 to 1974, Boyd had twenty tapestries woven by the Manufactura Tapecarias de Portalegre in Portugal, to cartoons produced from transparencies of the original pastels. These works, which have never been exhibited together in their entirety, continue to gather dust in the Hume storage depot of the National Gallery of Australia. Pont also includes in her catalogue a number of related drawings, unfinished pastel sketches and three oil paintings dealing with the theme of St Francis.

... (read more)I’ve had disturbing encounters with literature and film before: Reinaldo Arenas’s The Color of Summer (2000) and Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). Their unsettling nature lies in the ways in which they link sex and violence, and show their hooks in the political body and the (masculine) soul. Against oppressive régimes (whether socialist or capitalist), these texts engage in ambiguous defences of instincts that aren’t much prettier than the systems against which their anti-heroes rail.

... (read more)Rick Thompson reviews ‘Snapshot’ by Garry Disher, ‘A Thing of Blood’ by Robert Gott and ‘Dirty Weekend’ by Gabrielle Lord

Garry Disher’s Snapshot continues his police procedural series about Mornington Peninsula detective Hal Challis, begun with Dragon Man in 1999 (before that, Disher wrote an excellent series of thrillers about a career criminal named Wyatt, starting with Kickback, 1991). Snapshot is 100 pages longer than Dragon Man, but, paradoxically, it is much more pared back, leaner and smarter about what a police procedural (PP) can be.

... (read more)‘Write about what you know.’ This is probably good advice for aspiring writers. Whether it serves equally well for academics turning their hand to prose fiction is put to a severe test by Diane Bell’s first novel. Evil tells the story of an Australian feminist anthropologist who takes up a position at a small Jesuit college in the US. Like many ATNs (Academics Turned Novelists), Bell’s choice of genre is the academic mystery: it is no coincidence that one of the heroine’s favourite writers is Amanda Cross, otherwise known as the feminist critic Carolyn Heilbrun.

... (read more)