Poetry

In Dark Bright Doors, her tenth book, Jill Jones again explores a sense of contradiction. Perhaps in tune with this theme, Jones’s work here also shows two distinct types of poems, one that is part-hallucinatory, invoking the elements ‘air’, ‘water’ and an encompassing natural world of breath, rain, sky, sun, wings. In these poems, Jones attempts to describe the indescribable, to remark on or absorb the world’s beauty and peril. Many of these poems consequently feel insubstantial and vague, though that may be their aim – to suggest, to hint at something, to sketch in mystery, rather than to pin it down.

... (read more)Chris Wallace-Crabbe reviews 'An Anthology Of Modern Irish Poetry' edited by Wes Davis

For W.B. Yeats, Ireland was the place and source of poetry, even when he was living in Oxford or London. It was also a mythical figure, enabling of ardour and of song, the desirable ‘Cathleen, the daughter of Houlihan’; and it became a delicately evocative crepuscule, mocked by Brendan Kennelly when he opens a poem with ‘Now in the Celtic twilight decrepit whores / Prowl warily along the Grand Canal’. The very phrase ‘Irish poetry’ sounds like a pleonasm. For that moist country has long seemed synonymous with verse and folksong: just as Holland is synonymous with painting and France with elegant thought. Further, when I think of contemporary poets in our widespread language, Seamus Heaney must surely be the dominant world figure and Paul Muldoon the most verbally dazzling, even if our Les is close to Paul in this caper.

... (read more)An interview with David Musgrave

Tuesday, 01 June 2010Why do you write?

It’s not really a choice, but a necessity. Usually, it is the pressure of an idea or an emotional state that only seems to be satisfactorily released as words on a page. Sometimes, if there is a choice involved, it is in choosing not to write.

Are you a vivid dreamer?

Yes. A lot of my work originates in dream. Glissando began as a transcription of a dream I had longer ago than I care to admit.

... (read more)Prithvi Varatharajan reviews 'Walking on Ashes' by Winifred Weir

In 1914 men left for war expectant of a great adventure,’ Winifred Weir writes in the introduction to her poetry collection. ‘So many died. So many returned haunted, silent, desperate with what they had seen and endured.’ Walking on Ashes is Weir’s attempt to understand the effects of war on her family; her father and brother fought in World War I and World War II, respectively. The book, loosely chronological, contains dates of battles and their locations (‘Gallipoli’, ‘Passchendaele 1917’, ‘Amiens, France, 1918’). Some poems are out of order, suggesting that the sequence of events is less important than their overall consequence. In Walking on Ashes, time – like Weir’s father’s right arm – is shattered by war. The point of view is fluid, too: it shifts between father, mother, daughter, and son, as each has an experience to relate.

... (read more)Mid-career reinvention is an exciting thing. Ken Bolton’s poem ‘Outdoor Pig-Keeping, 1954 & My Other Books on Farming Pigs’, in Black Inc.’s The Best Australian Poems 2009, was the most surprising poem in the book. Where were the friends, artists and cafés? Where were the small ironies? A larger irony was at work. Bolton’s new book, The Circus, is something else again: a wry, sly and affectionate long poem nothing like Frank O’Hara – generally seen as Bolton’s guiding influence – and not much like Bolton’s Australian peers either. While much of Bolton’s poetry relies on a bemused first-person narration, relentlessly questioning what a poem or even a thought can do, The Circus is narrated in a shifting third person. It makes quite a difference.

... (read more)It is strangely affecting to see people’s lips moving as they sit silently reading to themselves. Apparently, when we read we can’t help but imagine speaking. Even silent reading has its life in the body: seeing words, the part of our brain that governs speech starts working. When we read poetry silently to ourselves, is it our own voice or the poet’s voice that we hear?

... (read more)Paul Kane reviews 'The Puncher & Wattmann Anthology of Australian Poetry' edited by John Leonard

‘Posterity is so dainty,’ complained the American essayist John Jay Chapman, ‘that it lives on nothing but choice morsels.’ Chapman was writing about Browning, whose work for his contemporaries meant life, not art. But, Chapman predicts, ‘Posterity will want only art’. It is a nice distinction when considering our penchant for anthologies. This daintiness goes all the way back to the first anthology, Meleager’s in ancient Greece, as the word itself means ‘flower gathering’, or simply a ‘garland’ or ‘bouquet’. We pick poems like flowers and arrange them in a book. The suggestion, of course, is that certain kinds of poems tend to get left out in favour of those that work best as stand-alone ornaments, giving us an unnatural notion of what’s actually out there growing in the fields.

... (read more)This is Tom Shapcott’s thirteenth individual collection of poetry (two Selected Poems have appeared, in 1978 and 1989) in a writing life that – at least for his readers – began with the publication of Time on Fire in 1961. It continues something of a late poetic flowering, which, to my critical mind, began with The City of Home in 1995. All in all, Parts of Us is no disgrace to its twelve predecessors.

... (read more)The subtle beauty of the title of Sarah Day’s new collection of poetry, Grass Notes, epitomises the lightness of touch and intensity that characterises the poems. This is a collection of observing what might otherwise be seen as slight or glancing, yet that offers powerful prisms of insight. In a Whitmanesque mode, Day’s perspective not only looks up from the grass into the vastness of the world, but also looks at the grass itself, the unexceptional yet foundational ground of all perception and experience. Perhaps as the poet scribbles ‘notes’ in that grass, there is also an echo of Wordsworth and post-romantics such as Judith Wright or Mary Oliver. The title also chimes homophonically with the idea of the musical ‘grace note’, that small, quick, note that runs into the next and, in its delicacy, makes that central sound, or image, both more appealing and more complex. In Day’s work, it is the delicacy of such lateral images, often derived from close consideration of the natural world, that complicates and enriches the ideas at work within the poems.

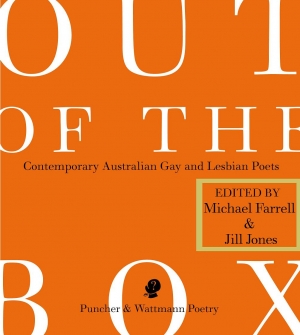

... (read more)Gregory Kratzmann reviews 'Out Of The Box: Contemporary Australian gay and lesbian poets' edited by Michael Farrell and Jill Jones

Does the title of this anthology, heralded by its editors as the first collection of Australian gay/lesbian/queer poetry, refer to the myth of Pandora’s pithos? Hesiod’s version of the story, which sees Pandora as the unleasher of all manner of evils on the (‘rational’/patriarchal) world, has been interrogated by feminist scholars who see Pandora in an older incarnation of ‘gift-giver’, bestower of plenitude, crosser of boundaries. Or does ‘Out of the Box’ have a more colloquial sense – ‘exceptional’, ‘surprising’? Whatever the reasoning behind the title, Michael Farrell and Jill Jones have made choices which should provoke debate (among other things) about gay and lesbian identity and community, and about the relationship between poet and reader.

... (read more)