Long Day’s Journey into Night

Jeremy Herrin’s London production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night opens with a scene of such quiet intimacy it is tempting to think that the audience has been admitted early. Actors Brian Cox and Patricia Clarkson are as great a drawcard as the play itself. This is a perfect pairing for a work whose reputation as a masterpiece continues unabated. Theirs is a performance of mutual, muted delight, one that’s supported by Herrin’s absorbing restraint, an atmosphere that invites concentration and empathy. From the outset, we are transfixed – and what a spell Cox and Clarkson cast! But will it weave its magic for a modern audience?

Much has been written about the play’s autobiographical nature. O’Neill (1888-1953) left instructions for it not to be published until twenty-five years after his death. Less than three years after his death, it was performed, earning the Nobel Laureate his fourth Pulitzer Prize for drama, a total that has yet to be exceeded. The play enjoys a reputation beyond the theatre that few others do. Its epic, historical status is reason enough to buy a ticket and go on the journey – a long one that leads the audience slowly through the gathering afternoon shadows of life with the Tyrone family. There will be solemn applause at the end, tinged with a certain mystification. Haven’t we just witnessed something beyond our reach? For this is the dramatisation of emotion, a production propelled by minimal action, a staging of stasis, remote and bewildering, but resonant too with the demons in our own lives – or those of others, if we’ve been fortunate enough to have thus far escaped them.

The subject matter, for a play set in 1912, feels contemporary: grief, addiction, family friction, with strong supporting players, isolation, truth, memory, art, time, fate, religion, regret and hope, progressively woven into the text. This is an examination of family and the piercing contradictions that support it. We begin with a depiction of the long, devoted love of husband and wife, their quiet delight in each other, their concern about their sons. The emotional territory feels familiar and yet something enigmatic lurks beneath the surface, something that suggests that the couple’s tenderness is tenuous, that the unadorned walls of their unlived-in house could, at any moment, fall away, as indeed they do.

It is tempting to imagine that the play will centre around Cox’s portrayal of James Tyrone, the family patriarch. However, in this production, the director places Clarkson, as James’s long-time wife, Mary, at the heart of the narrative, thereby allowing her contained performance, one fuelled by passive energy, to dominate the stage. Even Cox’s forceful performance shifts and shines in relation to Clarkson, a subtle depiction of a man doing battle between love and fear, oscillating beneath her gaze. When Mary is off stage, the men speak repeatedly of her return; in her absence, stories about her life light up the shadowy parlour where the play takes place. Clarkson’s performance, an absorbing navigation between strength and vulnerability, becomes a lightning rod for all the other players.

Mary’s precarious mental health is prefigured by the fog surrounding the house. At the play’s opening this is quite literal. ‘We must set to before the fog comes back.’ At the end it is metaphysical, referring to Mary’s mental state, the fogging of her mind, as the morphine, she has been at pains to give up, or not – this is intriguingly unclear – takes hold again. As the self-confessed,‘dope fiend’ mother finds her voice in monotone, all expression is leeched from her character. Her close to silent ramblings are disconcerting, a veritable staging of grief and loss; a longing for some impossible merger between performance and piety; a desire to be good, better, somewhere beyond the yoke of failed mother. This is the production’s great achievement: that through a woman’s suffering we open a door to the family’s failing, one so great it takes on the veil of tragedy.

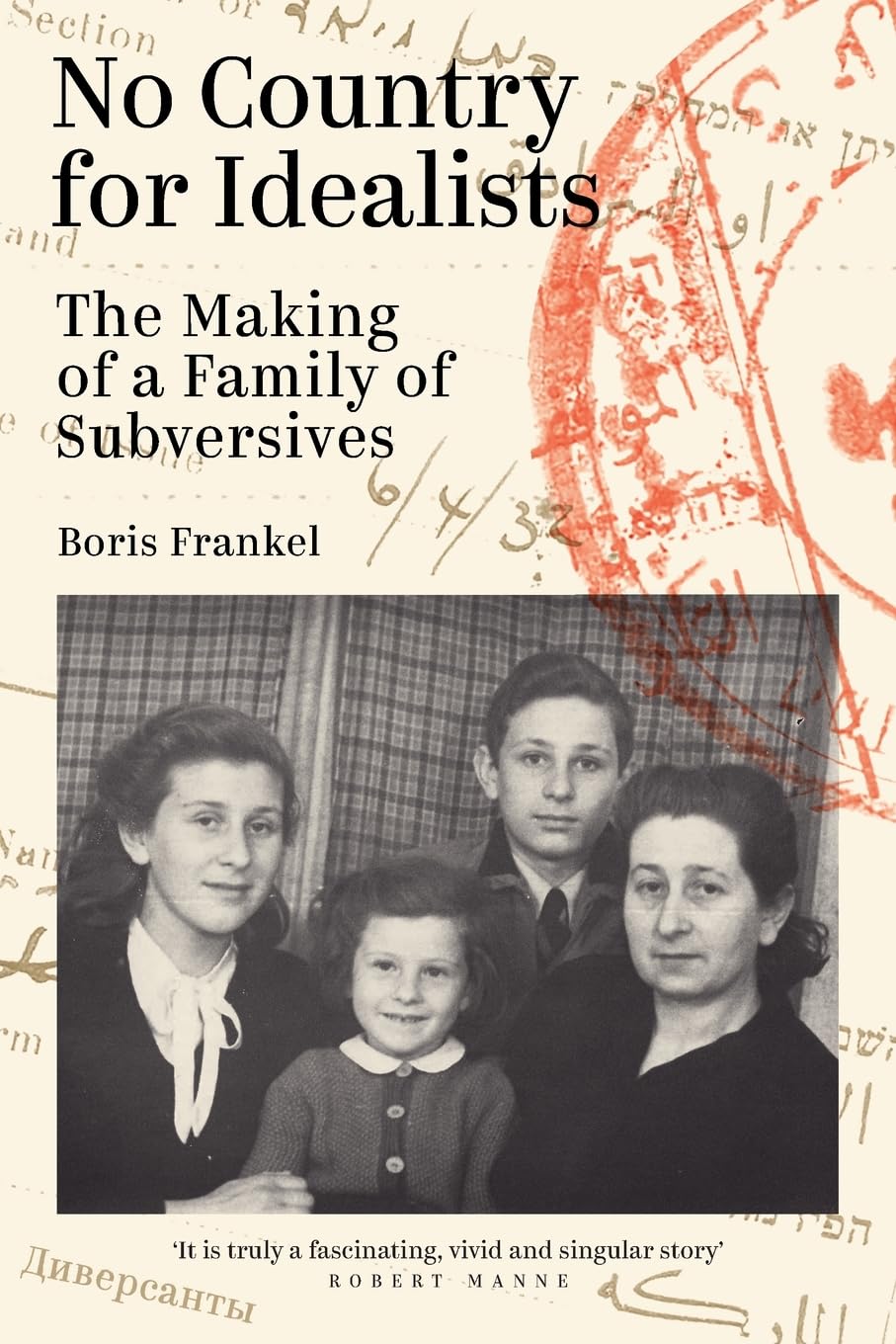

Daryl McCormack as James Tyrone Jr. (photograph by Johan Persson)

Daryl McCormack as James Tyrone Jr. (photograph by Johan Persson)

The heart of this tragedy is the sins of the fathers visited on the sons. The eldest, Jamie – played by Daryl McCormack in a heartbreaking performance of a young man struggling to reconcile his feelings for his brother – is an alcoholic actor, ravaged by a jealousy so profound it makes him, paradoxically, a sympathetic character. Laurie Kynaston, as the younger Edmond, is a delicately nuanced poet and would-be alcoholic who is suffering from consumption. Tyrone, an actor with financial success but no artistic integrity, all but admits to having led his sons to their fate, but in Mary’s eyes his greater sin was his insistence on her accompanying him on tour, leaving their young sons at home, the catastrophic consequences of which they are still all paying for.

Lizzie Clachan’s set is a space that says house more than home. From the outset, the bare walls and austere furniture speak of lack. It is a place with nowhere to hide, where everything is hidden. This is the physical incarnation of the emotional state. The action, though minimal, is in service to Jack Knowles’s ghostly lighting: the functional chairs, the unadorned table, a set that seems to expand the space by suggesting what’s beyond. There is no light in the hallway, no summoning home. The upstage piano is the only concession to the outside world. This is a fearful place of fog, falling, and regret.

All four characters are fatally flawed, but they are neither vilified nor exculpated. Theirs is a powerful drama where love and hate are aligned, where an articulate family of performers battles life with striking insight. Memories are untrustworthy and time wayward, collapsing the past with the present, the present with the future. The audience must rely on the unreliable accounts of addicts, alcoholics, and actors – all suspiciously lumped together – and yet this is where Long Day’s Journey into Night finds its way to a contemporary audience, in the complex and contradictory ways the characters respond to their circumstances and one another.

A star comic turn by Louisa Harland, as maid Cathleen, brings welcome humour to a house devoid of mirth. The lightening of spirits is only found in a whiskey bottle, the appreciation of which Cathleen exploits to the audience’s great delight. But the character serves another purpose too. It is a performance of a performance: we see Harland as Cathleen playing a part for Mary. Parlour entertainment, arrived at with the aid of whiskey, an affectionate indictment of the actor’s craft, a subject examined throughout, one that pits Shakespeare with Baudelaire to pose the question; what is worthy to be performed? For Tyrone, the answer is Shakespeare. His personal tragedy is not the death of his infant son but that he wasn’t ‘the finest artist I might have been’. His decision to squander his talent fills him with morbid regret. He knows only too well the value of a dollar, something he insists his two sons should learn. It is the price of his future, the price of all their futures; artistic endurance will not be vouchsafed to any of them.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night – completed in 1941 – was always set in the past. Jeremy Herrin’s production, as the script dictates, is set thirty years beforehand. It remains a work of realism, one in which the action springs from the dramatization of the psychological, but here the focus has the filmic quality of a close-up. With Cox and Clarkson, we witness performances so subtlety nuanced we almost forget they are happening on a stage. We are enthralled by their deep emotional integrity, alive as they are to some private interior world, terrain that feels wholly contemporary.

It is possible that O’Neill’s verbosity, his unhurried pace and frequent use of monologue, may leave a small gulf between stage and audience, one that will be spanned by some but not by others. Ultimately, the chemistry between all five actors is engrossing, at times mesmerising. The sense of wonder at Clarkson’s extraordinary final monologue – a tender evocation of Mary’s journey from girlhood to womanhood – was profound. Perhaps through the bank of talk, through paths of pain and wretchedness., we too found catharsis. Perhaps, for a moment, we remembered our own loves and happiness – and magic. I think we found that too.

Long Day’s Journey into Night (Second Half Productions) continues at the Wyndham Theatre in London until 8 June 2024. Performance attended: 17 April.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.