Autobiography

Autobiography is based on a paradox. It is a generic representation of identity, but identity and genre appear to be antithetical. If we conventionally think of our identity as unique (singular, autonomous and self-made), how then can the presentation of that identity be generic? How, when narrating our lives, can we be both singular and understandable? Does narrating a life presuppose a way of writing (that is, a genre) that will make it recognisable as a story of a life? And how individual can we be, given that we are social animals? We live in families, form attachments and belong to institutions. How much is identity a case of identifying with others?

... (read more)Ever Yours, C.H. Spence: Catherine Helen Spence’s an autobiography (1825–1910), diary (1894) and some correspondence (1894–1910) edited by Susan Magarey

by Elizabeth Webby •

My Spin On Cricket by Richie Benaud & Out Of My Comfort Zone by Steve Waugh

by Brian Matthews •

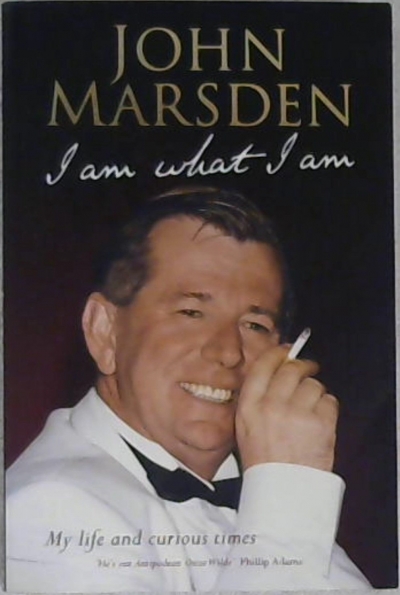

I Am What I Am: My life and curious times by John Marsden

by Robert Reynolds •

A Tuesday Thing by Kate Shayler & God's Callgirl by Carla van Raay

by Joy Hooton •

Bud: A life by Charles 'Bud' Tingwell (with Peter Wilmoth)

by Brian McFarlane •