Archive

The Patrician and The Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the making of Australian history by John Thompson

The Wayward Tourist: Mark Twain's adventures in Australia by Mark Twain, with an introduction by Don Watson

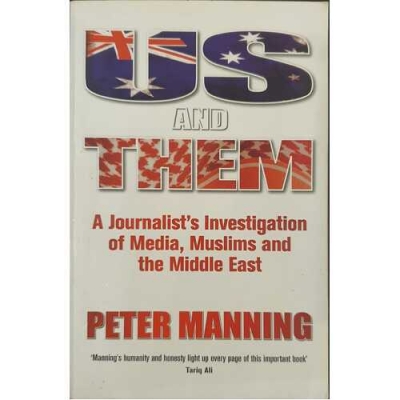

Us and Them: A journalist’s investigation of media, Muslims and the Middle East by Peter Manning

Donald Friend (1915–89) was one of Australia’s most prolific and widely travelled artists. Forty-four of his diaries are held in the National Library of Australia’s Manuscript Collection (individual diaries are held by the National Gallery of Australia and the James Hardie Library of Australian Fine Arts at the State Library of Queensland). The National Library also has items that are part of the important body of work that Friend produced in handcrafting thirteen lavishly illustrated manuscripts, largely in the last two decades of his life: ‘Birds from the Magic Mountain’; ‘Ayam-Ayam Kesayangan, Volume 3’; and ‘The Story of Jonah’ and ‘Bumbooziana’. These projects saw him develop the skills that he had honed for nearly forty years, in his illustrated diaries and earlier publishing ventures, into a highly sophisticated artistic practice, not unlike that of a medieval calligrapher but with the licence to do as he wanted.

... (read more)Southerly edited by David Brooks and Noel Rowe & Griffith Review 13 edited by Julianne Schultz (with Marni Cordell)

80 Great Poems: From Chaucer to now edited by Geoff Page

Those who come after

Nine months ago, in association with the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL), ABR announced the creation of a major new annual essay prize. In doing so we were conscious of the importance of the genre and of ABR’s long commitment to its preservation and promulgation. We set out to attract entries from the widest range of Australian writers (not just celebrated essayists). In order to entice a distinguished field, the Calibre Prize was valued at $10,000.

... (read more)