Archive

Unfinished Journey: Collected Poems 1932-2004 by Michael Thwaites

Papunya: A place made after the story: The beginnings of the Western Desert painting movement by Geoffrey Bardon and James Bardon

Heat 8 edited by Ivor Indyk & Life Writing Vol. 1 No. 2 edited by David McCooey

Loose Lips edited by Lauren Finger et al. & True North edited by Marain Devitt

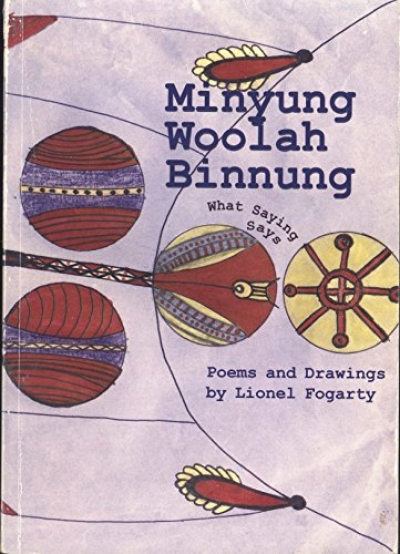

Minyung Woolah Binnung by Lionel Fogarty & Smoke Encrypted Whispers by Samuel Wagan Watson

A Win and A Prayer edited by Peter Browne and Julian Thomas & Run Johnny, Run by Mungo MacCallum

Crime Fiction by Stephen Knight & The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction edited by Martin Priestman

Day I – new suitors

The mountain thinks: Wilson, eh? Finally he comes. About time. The trucks stop on the north side where the Rongai route begins and Kilimanjaro’s powdered skirt tumbles out of Tanzania into Kenya. Her lower folds are less sensitive, but she still feels us among the thousands. In her stones she weighs our upward love and thinks: How much do you really want me? We start late and pad steadily from 1900 metres on the trail’s seamy musk with no perspective on the summit. Above us, only a shrug of fat hills and cloud. Kilimanjaro’s broad, high face (all ice-lashes and airless hauteur) is a vast four kilometres further up. Emmanuel tells us to walk polepole (slowly, gently). ‘Like walking your girlfriend home,’ he says.

... (read more)