Archive

The Sydney Morning Herald has been ‘Celebrating 175 Years’ all year. The words adorn every front page; the Herald ran a number of commemorative features to mark the actual anniversary on April 18; and The Big Picture: Diary of a Nation, consisting of essays by journalists and photographs from the Herald’s magnificent photographic library, has been published (see John Thompson’s review in the March issue).

... (read more)Tasmanian Devil: A Unique and Threatened Animal by David Owen and David Pemberton

Making And Breaking Australian Universities: Memoirs of an academic life in Australia and Britain 1936–2004 by Bruce Williams

Memory, Monuments And Museums: The past in the present edited by Marilyn Lake

Singing Australian: A History of Folk and Country Music by Graeme Smith

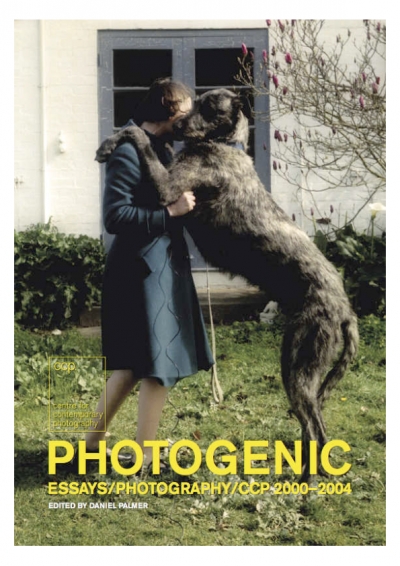

Photogenic: Essays/photography/ccp 2000-2004 edited by Daniel Palmer

After attaining a low-luminosity arts degree, I worked for a year as a handyman in my university’s Research School of Physical Sciences. This was in 1972, when the new particle accelerator was being installed in its massive concrete tower; its assembly made my humble handyman job one of the most intriguing and happy employments I have had. We bolted together the sandblasted steel pipes for the SF6 (sulphur hexafluoride) coolant, first larding their joints with gaskets of white gunk. In a lofty workshop dominated by the monstrous ex-Krupps steel mill (a German war reparation), we hefted the odd magnetron on chainblocks that our master-craftsmen might more conveniently prepare it for installation. We crawled into the cavernous interior of the accelerator’s ‘tank’ to grind at weld-burrs until the steel surface had no tiny irregularity to which the fourteen million volts intended for the apparatus could distractingly zap. To this smooth surface we then applied a silver paint until we stood, spattered angels encompassed by our weird reflective heaven. We watched the precision tubes being installed through the centre of this tank by lanky experts from Wisconsin, knowing how, within these conduits, the particles were to be accelerated by that impressive voltage toward targets the size of my thumbnail in collisions that would explain the universe finely.

... (read more)