Archive

The Spruiker’s Tale by Catherine Rey (translated by Andrew Riemer)

by Denise O'Dea •

Mixed Relations: Histories and stories of Asian–Aboriginal contact in north Australia by Regina Ganter (with Julia Martinez and Gary Lee)

by Tim Rowse •

Timing Is Everything: A life backstage at the opera by Moffatt Oxenbould

by John Slavin •

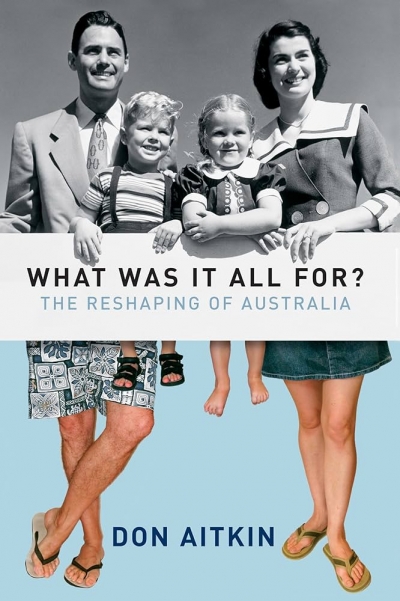

What Was It All For? by Don Aitken & Australia Fair by Hugh Stretton

by Dennis Altman •

Eyewitness: Australians write from the front-line by Garrie Hutchinson

by Martin Ball •

Australian Dictionary of Biography: Supplement, 1580–1980 by Christopher Cunneen

by Paul Brunton •

Australia Imagined: Views from the British periodical press, 1800–1900 edited by Judith Johnston and Monica Anderson

by David Carter •