Archive

The Ice and the Inland by Brigid Hains & Australia’s Flying Doctors by Roger McDonald and Richard Woldendorp

by Libby Robin •

Australia’s Democracy by John Hirst & The Citizens’ Bargain edited by James Walter and Margaret Macleod

by Patricia Grimshaw •

To the Islands by Randolph Stow & Tourmaline by Randolph Stow

by Thomas Shapcott •

Broken Song: T.G.H. Strehlow and Aboriginal possession by Barry Hill

by Frances Devlin-Glass •

Crime of Silence by Patricia Carlon & The Unquiet Night by Patricia Carlon

by Sydney Smith •

The Commonwealth of Speech: An Argument about Australia’s Past, Present and Future by Alan Atkinson

by Beverley Kingston •

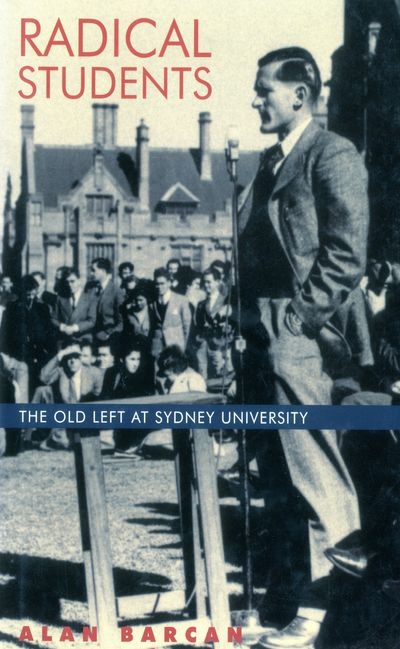

Radical Students by Alan Barcan & The Diary of a Vice-Chancellor by Raymond Priestly (ed. Ronald Ridley)

by Michael Crennan •