Archive

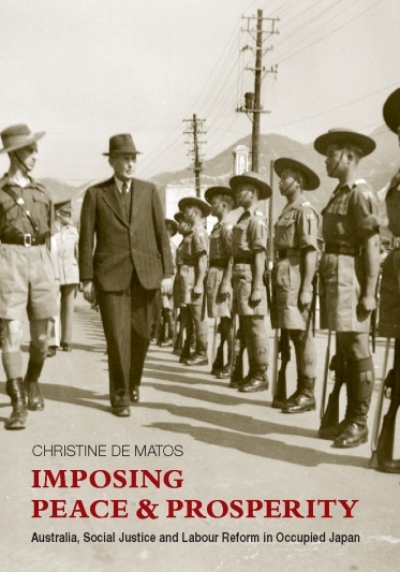

Imposing Peace and Prosperity: Australia, Social justice and Labour reform in occupied Japan by Christine de Matos

by Wayne Reynolds •

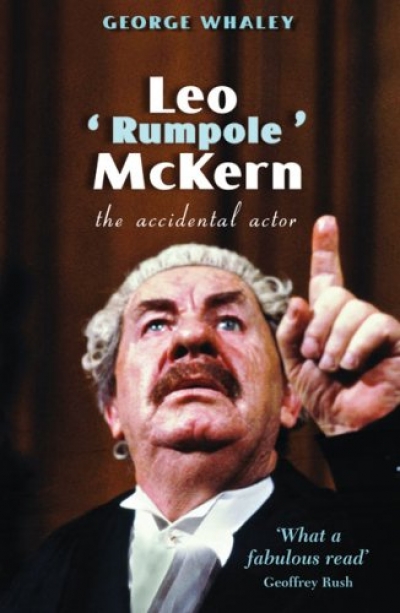

Leo ‘Rumpole’ McKern: The accidental actor by George Whaley

by Brian McFarlane •

Freefall

must be like this,

The Beginner’s Guide to Living by Lia Hills & Posse by Kate Welshman

by Ruth Starke •