Review

Margaret Michaelis: Love, loss and photography by Helen Ennis

by Evelyn Juers •

Black Diamonds and Dust by Greg Bogaerts & Sandstone by Stephen Lacey

by Allan Gardiner •

Motherhood: How should we care for our children? by Anne Manne

by Cathy Sherry •

The Tao of Shepherding by John Donnelly & The Lost Tribe by Jane Downing

by Cheryl Taylor •

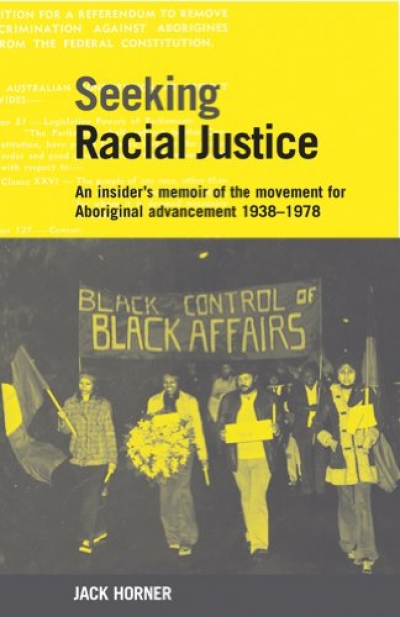

Seeking Racial Justice by Jack Horner & Black and White Together by Sue Taffe

by Matthew Lamb •

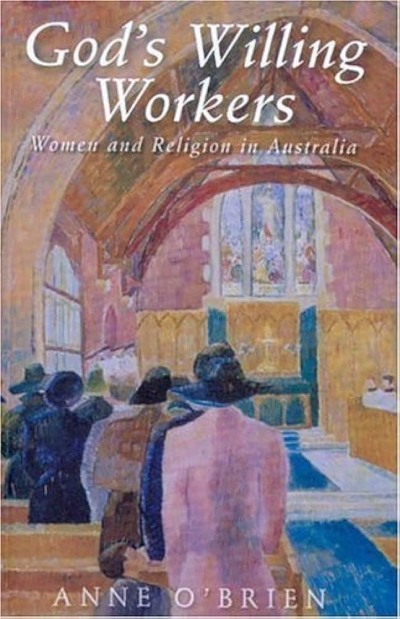

God’s Willing Workers: Women and religion in Australia by Anne O'Brien

by Pamela Bone •