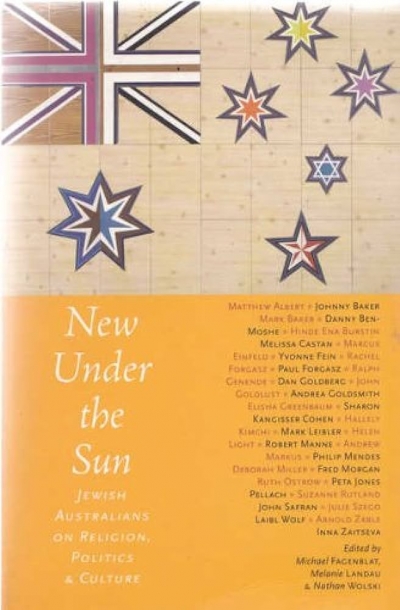

This significant anthology consists of thirty-three articles by Jewish Australian scholars, lawyers, writers, educators, rabbis, journalists and other high achievers, prefaced by a thoughtful and wide-ranging introduction by the editors. Many of the contributors are distinguished in their fields and prominent in public life. The editors have cast the volume from a ‘perspective of commitment and belonging’, with the conviction that ‘challenge and critique when offered by committed members rather than hostile outsiders is often the most useful form of reckoning with ourselves’. The disjunction is troubling (I think I may be a hostile insider), but its effect does not diminish the interest of the collection. The book’s focus is narrower than its subtitle suggests: these are not just passing reflections by some Jewish Australians: each contribution is centrally about some aspect of the religion, politics and culture of Jewish Australians. As such, it provides a useful and authoritative synopsis of the progress, state and thoughts of many Australian Jews today. No single essay sparkles brilliantly, and a few are alarmingly deficient in serious thought; nevertheless, this is a big, rich, diverse collection deserving of wide public attention.

...

(read more)