Robert Phiddian

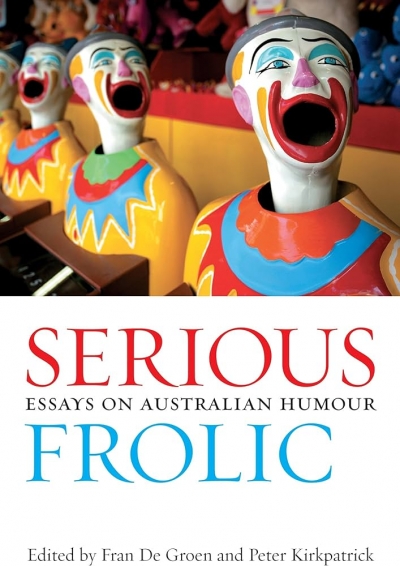

Serious Frolic: Essays on Australian Humor edited by Fran de Greon and Peter Kirkpatrick

by Robert Phiddian •

Comic Commentators: Contemporary political cartooning in Australia edited by Robert Phiddian and Haydon Manning

by Iain Topliss •

Pacifism and English Literature: Minstrels of peace by R.S. White

by Robert Phiddian •

Man of Steel: A Cartoon history of the Howard years edited by Russ Radcliffe

by Robert Phiddian •

The Wayward Tourist: Mark Twain's adventures in Australia by Mark Twain, with an introduction by Don Watson

by Robert Phiddian •

Poetry and Philosophy from Homer to Rousseau: Romantic souls, realist lives by Simon Haines

by Robert Phiddian •