Thames & Hudson

Black Duck: A year at Yumburra by Bruce Pascoe with Lyn Harwood

by Seumas Spark •

2022: Reckoning with power and privilege edited by Michael Hopkin

by Joel Deane •

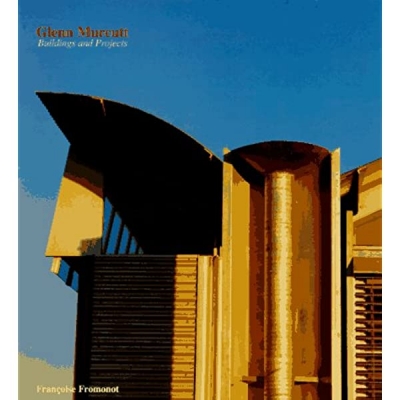

Glenn Murcutt: Buildings + projects 1962-2003 by Françoise Fromonot, translated by Charlotte Ellis

by Dimity Reed •

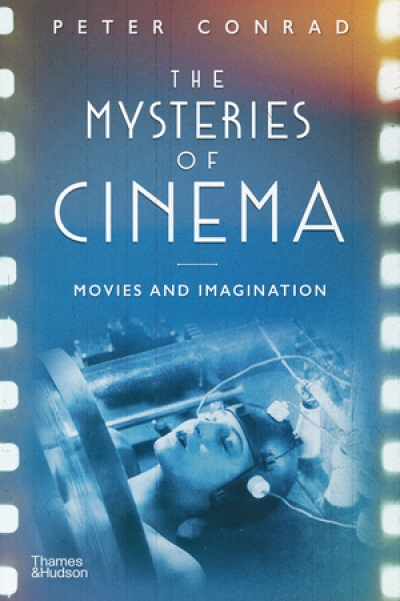

The Mysteries of Cinema: Movies and imagination by Peter Conrad

by James Antoniou •

After The Australian Ugliness edited by Naomi Stead, Tom Lee, Ewan McEoin, and Megan Patty

by Jim Davidson •