Archive

The Running Man by Michael Gerard Butler & By The River by Steven Herrick

by Michael Shuttleworth •

War Is Not the Season for Figs by Lidija Cvetkovic & Modewarre by Patricia Sykes

by Michelle Borzi •

Frontier Justice: A History of the Gulf Country to 1900 by Tony Roberts

by Nicholas Jose •

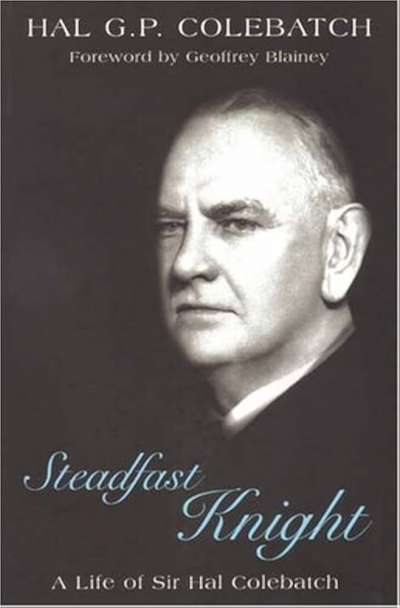

Steadfast Knight: A life of Sir Hal Colebatch by Hal G. P. Colebatch

by Paul de Serville •

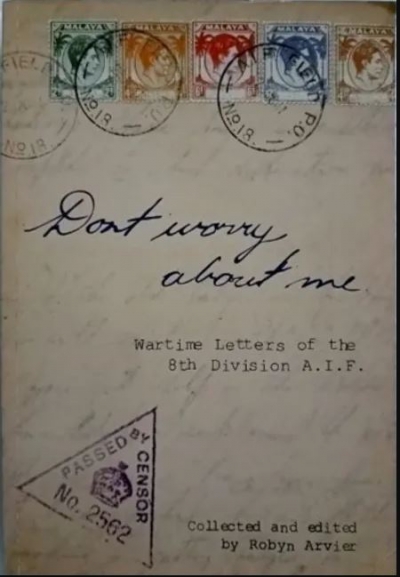

Don't Worry About Me edited by Robyn Arvier & Hellfire by Cameron Forbes

by Rod Beecham •

Fold out evenings, chairs in the street.

‘See Iridium?’ Making out the satellite pantheon:

efficient gods that do return our prayers

(small voices cast across our desert spaces)

like stars —

like Clint Eastwood

riding impassive

through our networks of desire.

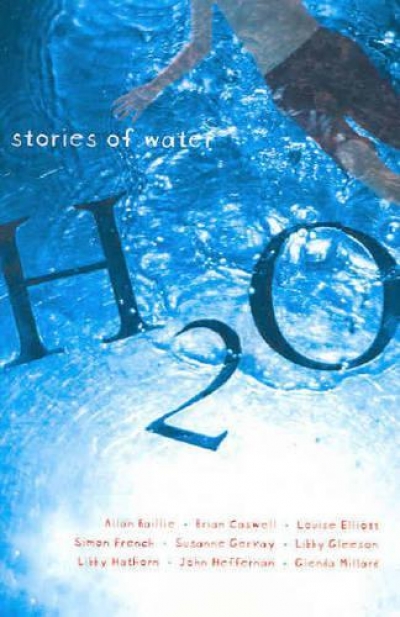

... (read more)H2O edited by Margaret Hamilton & And the Roo Jumped Over the Moon edited by Robin Morrow, illustrated by Stephen Michael King

by Sherryl Clark •