Archive

The Retreat of the Elephants: An environmental history of China by Mark Elvin

by Antonia Finnane •

The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy by Jussi Hanhimäki

by Barry Jones •

An Eye For Photography: The camera in Australia by Alan Davies

by Isobel Crombie •

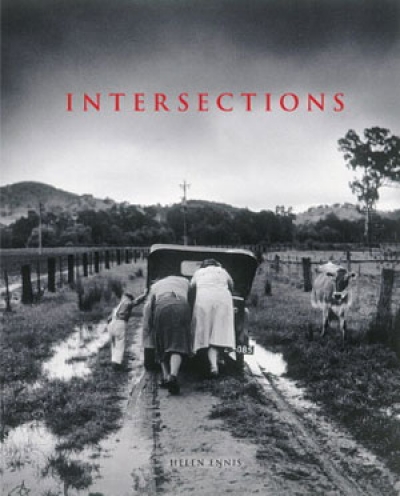

Intersections: Photography, history, and the national library of Australia by Helen Ennis

by Julie Robinson •

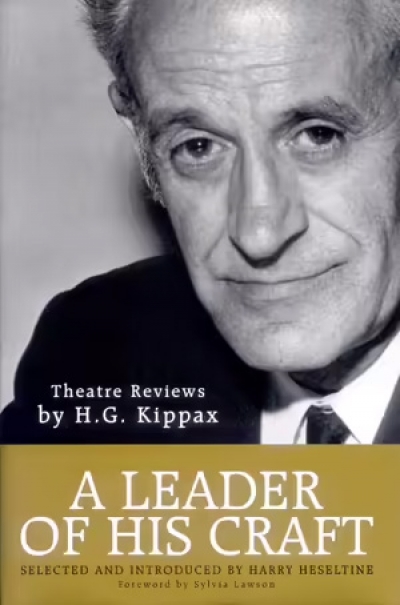

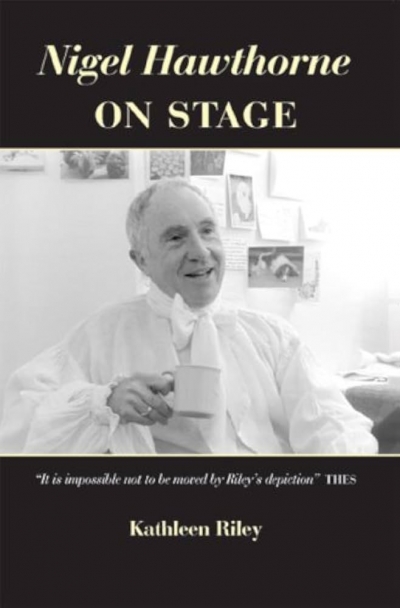

A Leader of His Craft: Theatre reviews by H.G. Kippax edited by Harry Heseltine

by Ken Healey •

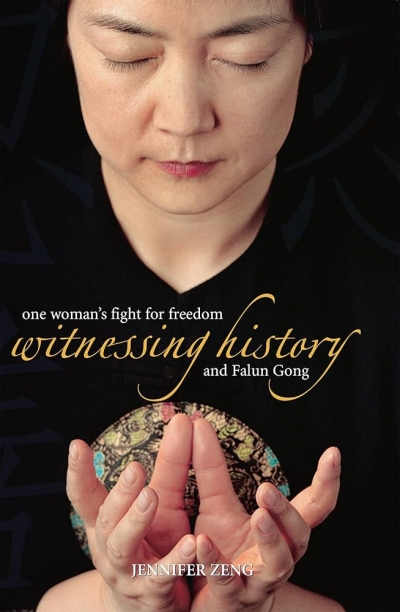

Witnessing History: One woman’s fight for freedom and Falun Gong by Jennifer Zeng

by Helene Chung Martin •

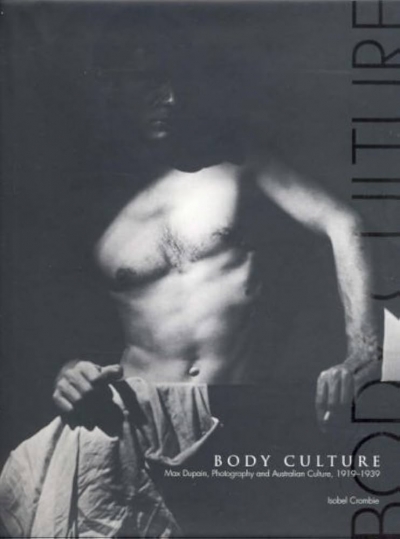

Body Culture: Max Dupain, photography, and Australian culture, 1919–1939 by Isobel Crombie

by Ian North •