Children's and Young Adult Books

Life’s not easy when … (fill in the blank according to your main story issue). It is a line that appears frequently on back covers and in press releases for junior fiction. But life is getting a lot easier for parents and teachers of reluctant readers who would far rather race around with a ball than curl up with a book. With the arrival of the sports novel, they can now read about somebody else racing around with a ball – or surfing, swimming, pounding the running track, wrestling, or cycling (the genre covers a wide field). Balls, however, seem to predominate. And problems. Life isn’t easy for publishers without a sports series. Hoping to emulate the success of the ‘Specky Magee’ books written by Felice Arena and Garry Lyon, publishers have been busy throwing authors and sport stars together, one to do the creative business, and the other to add verisimilitude and sporting cred.

... (read more)History has never been so much fun,’ says the blurb of one of the books reviewed below. Welcome to the twenty-first century. Work is fun. History is fun. Writing is fun. Writing history must therefore be really fun!

... (read more)Here are five reasons why there is a literacy crisis in Australia. It is not about teacher-training; it’s about appallingly conservative publishing choices and the positioning of ‘reading’ as something that needs to be slipped under the radar of children’s attention, rather than celebrating it as one of life’s biggest adventures. What these novels share is a commitment to sport as a structuring narrative principle. Australian Rules, rugby union, netball, athletics, soccer: the sports and titles change, but the overall arc remains the same. In this respect, these books feel market-driven: generic responses to some global marketing division called ‘encouraging reluctant readers’. While this enterprise is not unworthy, the assumption that children who are not reading will be automatically attracted to novels about organised sport seems dubious.

... (read more)Young Murphy by Gary Crew, illustrated by Mark Wilson & 101 Great Killer Creatures by Paul Holper and Simon Torok, illustrated by Stephen Axelsen

The Astrolabe by Susan Arnott & Our Enemy, My Friend by Jenny Blackman

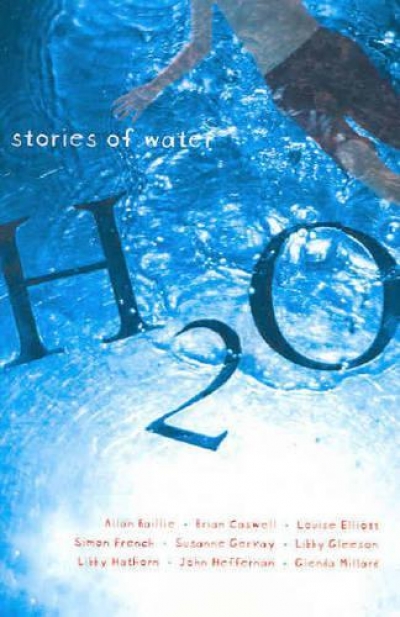

H2O edited by Margaret Hamilton & And the Roo Jumped Over the Moon edited by Robin Morrow, illustrated by Stephen Michael King

The authors of these four books use a narrative device common to much fantasy fiction: the notion of quest. Sometimes that quest requires a physical journey, and sometimes it involves searching for something closer to home, but the very process is almost invariably life-changing for the characters involved.

... (read more)