Melbourne Theatre Company

English Nobel Laureate Kazuo Ishiguro has had several works translated into film – notably The Remains of the Day (1993) and Never Let Me Go (2010) – but Melbourne Theatre Company’s Come Rain or Come Shine is the first stage musical based on his work. One of five short stories on the theme of music and nightfall that make up the collection Nocturnes (2009), it’s an odd little tale of friendship and failure that careens from the gently elegiac to the outright farcical, like F. Scott Fitzgerald via Michael Frayn.

... (read more)On paper, American playwright Adam Rapp’s The Sound Inside is an intriguing piece of writing. Bella Baird, a professor of creative writing at Yale University, ‘emerges from the darkness’ onto a nondescript stage and introduces herself. She speaks in the ‘heavily embroidered, figurative’ sentences that she dissuades her students from using, a liberty she allows herself standing here, alone in a park, ‘[talking] things out’.

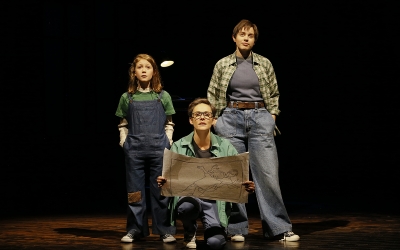

... (read more)Vladimir Nabokov, in his exquisite autobiographical work Speak, Memory (1967), says that ‘the prison of time is spherical and without exits’. It is an idea that animates Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron’s musical adaptation of Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home (2006), moving as it does in circular motions, enfolding its characters in an endless orbital spin through the years. Perhaps memory itself is like this, forever returning to our consciousness the painful and joyous things we’d thought we’d left behind, like moons in retrograde. It is no accident that the show’s opening number is titled ‘It All Comes Back’.

... (read more)As is often the case with Shakespeare, theories and counter-theories about the provenance of As You Like It (probably 1599 or early 1600) have floated around for centuries. One such theory posits that the play is Love’s Labour’s Won, the ‘lost’ sequel – or more accurately second part of a literary diptych – to Love’s Labour’s Lost (1595–96) and that As You Like It is actually the play’s subtitle. This would align with Shakespeare’s finest comedy, Twelfth Night, which has the subtitle What You Will. Take that as you like it and make of it what you will.

... (read more)Over the past decade or so, the centrality of fact in journalism, in political discourse, and in long-form non-fiction writing itself has taken a hit. The days are long gone when readers of The Washington Post could have confidence that the journalists who broke open Watergate had not only done due diligence but had chased every fact down the rabbit hole of governmental corruption. Now readers tend to gravitate to media organisations that confirm their own bias and dismiss the others as hubs of half-truths and outright lies. But what if the facts obscured rather than revealed the heart of a story? What if the facts got in the way of the mood, the texture, and the feeling of a real-life event? Is there any justification for deliberate or poetic inaccuracy in non-fiction? Lifespan of a Fact, a new play currently being presented by the Melbourne Theatre Company, has us wondering.

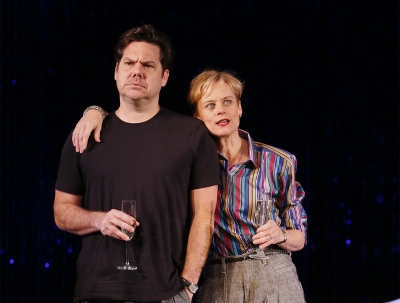

... (read more)Berlin, by Joanna Murray-Smith, is an intense, very wordy, imperfectly plotted, but nonetheless stylish play. ‘Stylish’ is a strange word to describe a play about young love sabotaged by tragic secrets and the legacy of the Holocaust. Shouldn’t it also be ‘heart-breaking’, ‘harrowing’, or at least ‘poignant’? Perhaps, but ‘stylish’ is the right word for a play – a thriller, in fact – that is also a swiftly argued essay on the difficulties faced by sensitive and ethical individuals who want to free themselves from the snares of history to make a new future.

... (read more)In the last decade there has been a welcome shift in our theatre ecology, with more main-stage companies keen to revisit classic Australian plays. Where once a new work by a local writer would have its run and then, no matter how acclaimed, disappear, rarely to be seen again outside of school and amateur productions, we are now being given another chance to experience some of these seminal plays, discovering not merely where we have come from as a country and as a culture but also, importantly, how we’ve changed.

... (read more)When attempting to cajole a compulsive hoarder into cleaning up, it’s advisable to start with the things are worth worth keeping, but it shouldn’t distract us from taking out the trash. Ubiquitous television and print personality Benjamin Law’s first foray into playwriting, Torch the Place, is one of four new works appearing in NEXT STAGE Originals, Melbourne Theatre Company’s new commissioning endeavour, the only one that doesn’t come from an established playwright. While there are several things to like in this début, there are a number that should be consigned to the skip.

... (read more)Judy and Johnny live a blissful 1950s life. While he readies himself for a day at the office, she twirls around the kitchen preparing his breakfast. They are, they declare, ‘sickeningly happy … utterly content’. The twist that comes at the end of the first scene of Home, I’m Darling has been heavily signposted in pre-publicity, so it’s not giving anything away to say that we are not in the 1950s at all.

... (read more)Argentine writer Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel Kiss of the Spider Woman seems to have shed most of its cultural specificity with each new iteration. Most people know it from the 1985 film that transposed the action to a Brazilian prison, for no conceivable reason other than the fact that the director was Brazilian (Héctor Babenco). The 1992 musical, with a book by Terrence McNally and music and lyrics by John Kander and Fred Ebb, goes a step further, and sets it in an undisclosed South American country – as if all political hells were the same, as long as they were subcontinental.

... (read more)