Text Publishing

A Hand in the Bush by Jane Clifton & Death by Water by Kerry Greenwood

by Jake Wilson •

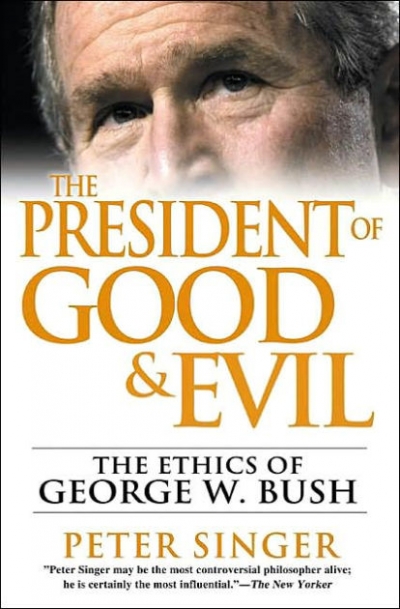

The President of Good & Evil: The ethics of George W. Bush by Peter Singer

by Raimond Gaita •

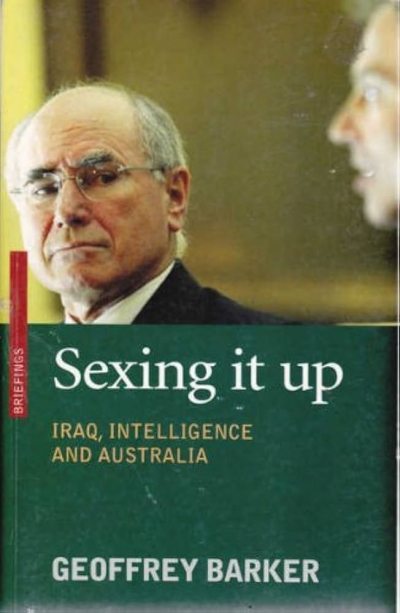

Sexing It Up by Geoffrey Barker & Why the War was Wrong edited by Raimond Gaita

by Nathan Hollier •

The Uncyclopedia by Gideon Haigh & Names From Here and Far by William T. S. Noble

by Fred Ludowyk •