Miegunyah Press

Possession by Bain Attwood & Shaking Hands on the Fringe by Tiffany Shellam

by Robert Kenny •

Nobody’s Valentine: Letters in the life of Valentine Alexa Leeper 1900–2001 by Marion Poynter

by John Rickard •

Gough Whitlam: A moment in history (Volume One) by Jenny Hocking

by Neal Blewett •

Graham Kennedy Treasures: Friends remember the king by Mike McColl Jones

by Sue Turnbull •

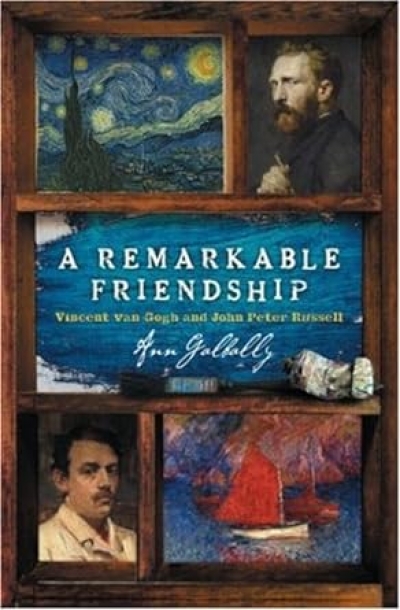

A Remarkable Friendship: Vincent Van Gogh and John Peter Russell by Ann Galbally

by Fiona Gruber •

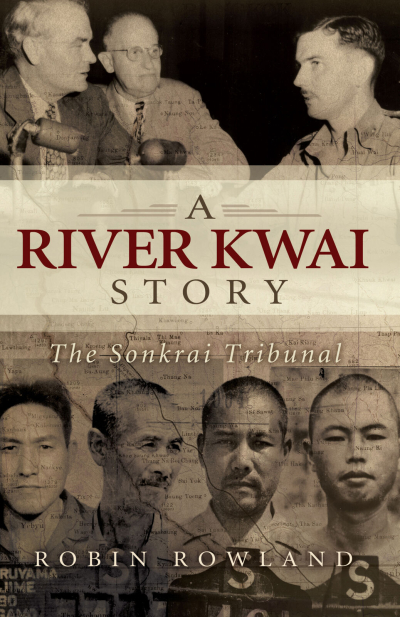

A River Kwai Story by Robin Rowland & The Men of the Line by Pattie Wright

by John Connor •

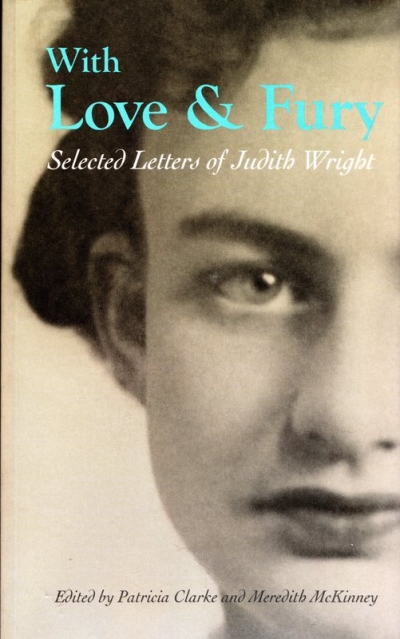

With Love and Fury edited by Patricia Clarke and Meredith McKinney & Portrait of a Friendship edited by Bryony Cosgrove

by Lisa Gorton •

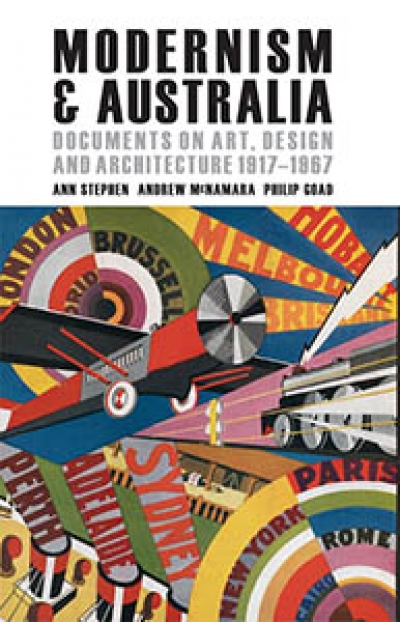

Modernism & Australia: Documents on art, design and architecture 1917–1967 edited by Ann Stephen, Andrew McNamara, and Philip Goad

by Anthony White •

B.A. Santamaria: Your most obedient servant: Selected Letters 1938–1996 edited by Patrick Morgan

by Brenda Niall •