Arts

I have been looking at the world through tartan frames recently, thanks to the current exhibition ‘For Auld Lang Syne: Images of Scottish Australia from First Fleet to Federation’ and its accompanying catalogue. Actually, to call it a catalogue doesn’t do it justice; its 330 pages ransack dozens of different angles of the Caledonian experience, with essays by ...

The Rijksmuseum used to be the dullest of the major European collections. It looked as though Ursula Hoff had painted all the pictures. An air of dowdiness hung over the massive building and crowded collections where the good and the great indiscriminately mixed in with the mediocre in warren-like galleries with an over-supply of the decorative arts.

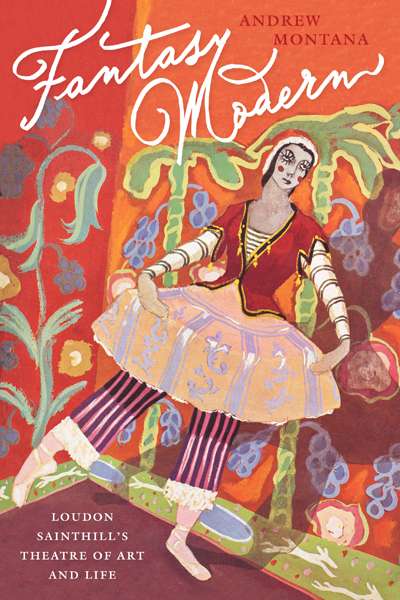

...Fantasy Modern: Loudon Sainthill's Theatre of Art and Life by Andrew Montana

With aching feet, bursting bladders, and the odd carrot for sustenance, Samuel Beckett’s famous pair of tramps have shuffled on to the stage of the Sydney Theatre for an extended run, though run is hardly the apposite word for this stationary duo. Perhaps one could call it an extended slump.

... (read more)