Review

People Power: How Australian referendums are lost and won by George Williams and David Hume

by Anne Twomey •

The Men Who Killed the News: The inside story of how media moguls abused their power, manipulated the truth and distorted democracy by Eric Beecher

Watching the denouement of Melbourne Shakespeare Company’s Hamlet, I was reminded of David Edgar’s 1980 stage adaptation of Charles Dickens’s The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby. Ensconced within the travelling theatrical company of Mr Vincent Crummles, Nicholas and his hapless companion Smike are cast in a production of Romeo and Juliet, Smike as the apothecary and Nicholas (of course) as Romeo.

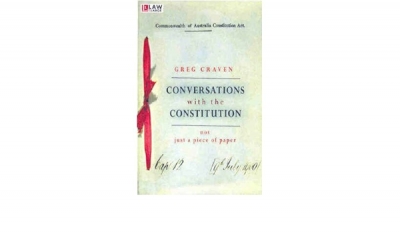

... (read more)Conversations With The Constitution: Not Just A Piece Of Paper by Greg Craven

by James Upcher •

In Search of John Christian Watson: Labor’s first prime minister by Michael Easson

by Lyndon Megarrity •

Vector: A surprising story of space, time, and mathematical transformation by Robyn Arianrhod

by Michael Lucy •

The Fatal Alliance: A century of war on film by David Thomson

by Kevin Foster •