Viking

Wasted: The true story of Jim McNeil, violent criminal and brilliant playwright by Ross Honeywill

by Murray Waldren •

And So It Went: Night thoughts in a year of change by Bob Ellis

by John Byron •

The Ghost at the Wedding: A true story by Shirley Walker

by Brenda Niall •

Shooting Balibo: Blood and memory in East Timor by Tony Maniaty

by Jill Jolliffe •

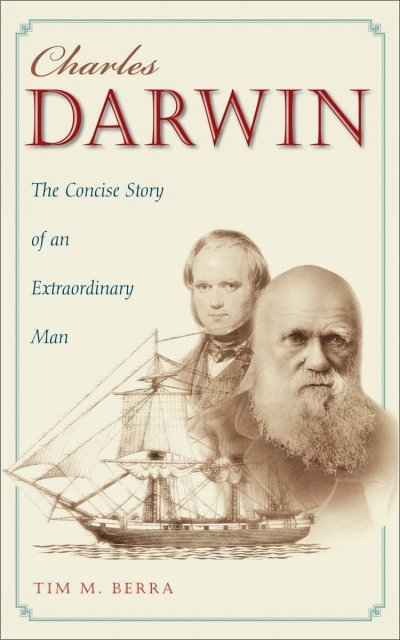

Charles Darwin by Tim M. Berra & Darwin’s Armada by lain McCalman

by David Lumsden •