The Conversation

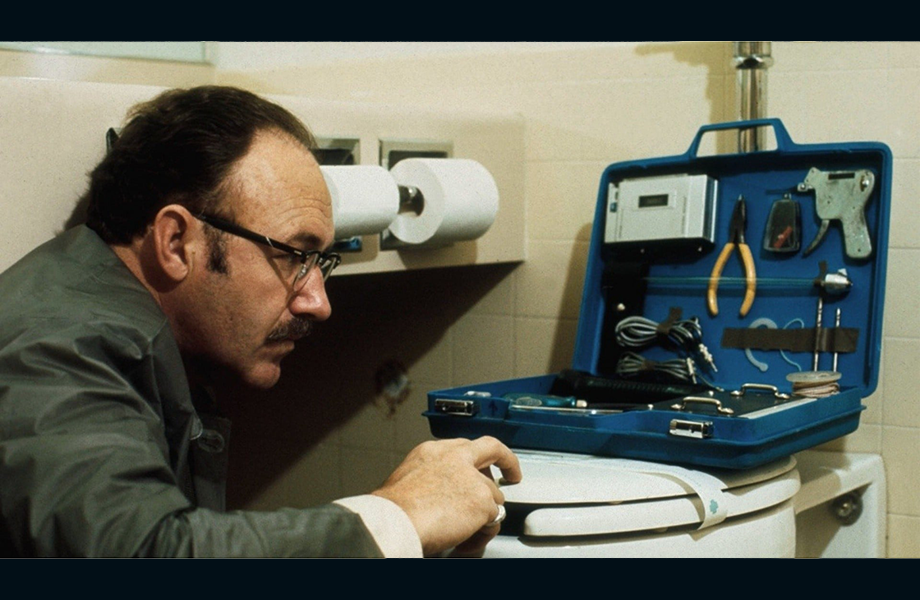

In the opening shot of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation – one of the great opening shots in cinema – a slow, telescopic zoom scans the lunchtime crowd on a sunny day in San Francisco’s Union Square. As if by accident, the camera settles on Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), a middle-aged man in a grey raincoat whom we may not have even noticed if it weren’t for a busking mime sidling over and beginning to mimic his movements. Harry walks off. The mime follows, trying to mine more material from his gait, but quickly grows bored and gives up. Right from the start, Harry Caul is apparently so unmemorable, so thoroughly nondescript, that he seems immune to parody.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.