Review

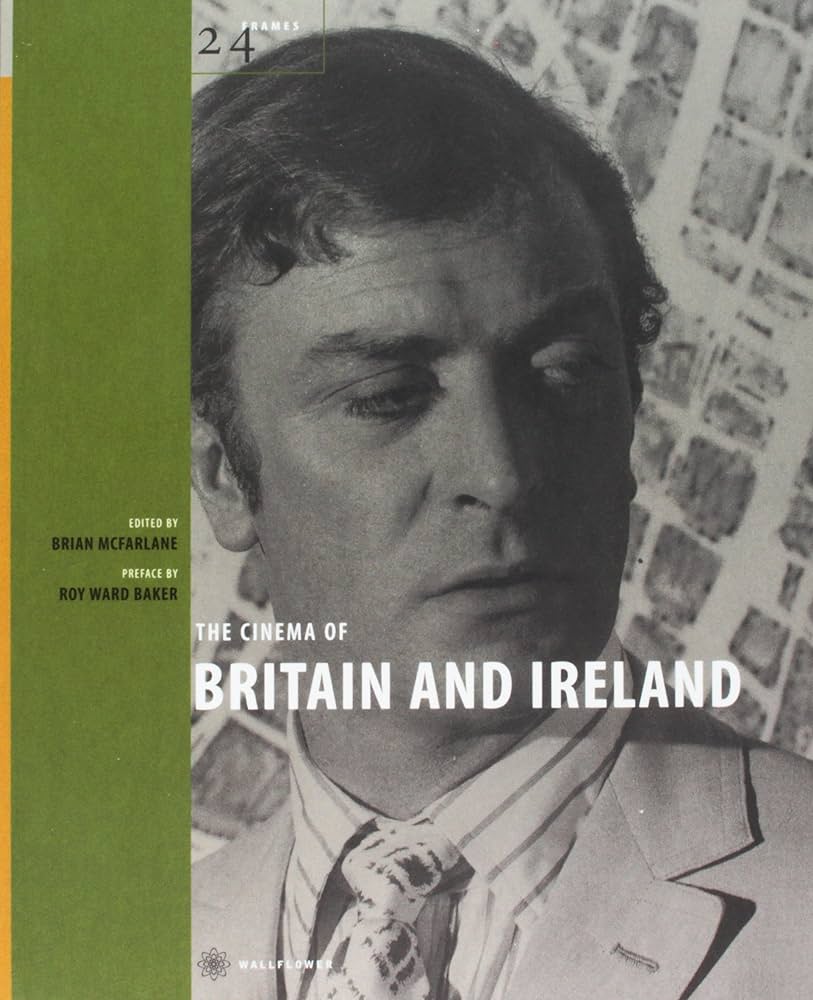

The Cinema of Britain and Ireland edited by Brian McFarlane

by Richard Johnstone •

Dating Aphrodite: Modern adventures in the ancient world by Luke Slattery

by Peter Steele •

Yarra by Kristin Otto & The Vision Splendid by Richard Waterhouse

by Mark McKenna •

Young Murphy by Gary Crew, illustrated by Mark Wilson & 101 Great Killer Creatures by Paul Holper and Simon Torok, illustrated by Stephen Axelsen

by Margaret Robson Kett •

Of Marriage, Violence and Sorcery: The quest for power in Northern Queensland by David McKnight

by Inga Clendinnen •

The Past Completes Me: Selected poems 1973–2003 by Alan Gould

by Martin Duwell •