Theatre

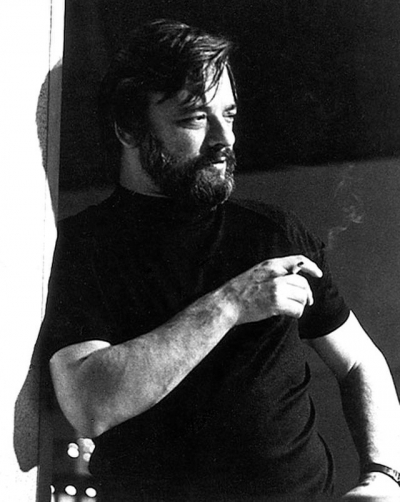

I’ve often wondered what it would be like to witness the extinguishing of a genius who not only defined an era or a movement but also ruptured an art form. Virtually nothing of Shakespeare’s death is recorded, so we are left to invent the dying of that light. Mozart’s funeral was infamously desultory, and Tolstoy’s swamped by paparazzi as much as by the peasantry. Stephen Sondheim, the single greatest composer and lyricist the musical theatre has ever known, died at his home in Connecticut on 26 November, and we who loved him feel the loss like a thunderbolt from the gods. Not because we’re shocked – he was ninety-one after all – but simply because we shall not see his like again.

... (read more)Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, first performed in 1599, is deeply interested in the difference between sleeping and wakefulness, if sleeping is equivalent to wilful ignorance and being awake means political consciousness. Characters throughout the play can’t sleep, won’t sleep, sleep on stage, are roused from sleep; they dream, and their eyes open and close, put to an eternal sleep. Before officially joining the conspiracy to murder Caesar in the Capitol, the play’s hero Brutus receives three letters from the conspirators Cassius and Casca entreating him to open his eyes to Caesar’s tyrannical aims: ‘Brutus, thou sleep’st; awake’. Once awake, it is his duty to ‘Speak, strike, redress’. The play’s language of sleep is strikingly similar to twenty-first century discourses of wakefulness – whether a woke sensitivity to issues of social justice, or the rioters at the United States Capitol shouting, ‘Wake up to the steal!’

... (read more)As is often the case with Shakespeare, theories and counter-theories about the provenance of As You Like It (probably 1599 or early 1600) have floated around for centuries. One such theory posits that the play is Love’s Labour’s Won, the ‘lost’ sequel – or more accurately second part of a literary diptych – to Love’s Labour’s Lost (1595–96) and that As You Like It is actually the play’s subtitle. This would align with Shakespeare’s finest comedy, Twelfth Night, which has the subtitle What You Will. Take that as you like it and make of it what you will.

... (read more)A Buddhist prayer wheel is a cylinder stuffed with sacred mantras and set on a spindle. Turning the cylinder is supposed to produce the same benefit as chanting the texts aloud. For true believers, contemplation of the endless turning of the wheel can be an aid to meditation and a way of drawing nearer to enlightenment. In nineteenth-century Europe, however, the wheel – dismissed by missionaries as a prayer machine – became a popular symbol for the withering effects of technology on the soul: an image of a hand-held mechanical device elevated to the medium of spiritual agency.

... (read more)On the evening of Wednesday, 16 October 1991, after the annual Valedictory Dinner at Melbourne University’s august Ormond College, the Master allegedly made unprovoked sexual advances to two female students. These incidents lead to a scandal which rocked the Melbourne establishment, caused the exit of the Master, and became the basis of Helen Garner’s hugely controversial exploration of sexual politics, class, and power, The First Stone (1995).

... (read more)The birds are twittering and tweeting (all puns intended) on Manor Farm. Industrial scaffolding leads up to a platform that cuts the minimalist set in two. The same metal barriers that are used to corral the crowds waiting for Covid-19 vaccinations criss-cross the floor of the stage. ‘Breaking News’ flashes across the cinema-sized screen that looms over what will soon be renamed ‘Animal Farm’.

... (read more)Broad Encounters’ A Midnight Visit – a touring multi-room immersive production – takes the life and works of Edgar Allen Poe as its inspiration. For Brisbane’s iteration, it transforms a soon-to-be-demolished building in Fortitude Valley into a funeral parlour and, beyond it, an uncanny, gothic dreamscape you explore at your own pace.

... (read more)About fifteen years ago, a group of British playwrights, disheartened by what they saw as a lack of ambition and scale in new plays, started a movement they dubbed ‘monsterism’. Their manifesto called for large-scale work with big casts and ideas in contrast with the two- and four-handed studio theatre plays proliferating in an atmosphere of economic and intellectual austerity. Watching Hibernation, Finegan Kruckemeyer’s new play for State Theatre Company South Australia, I was reminded of the monsterists and their still-relevant demands for a bigger, bolder theatre.

... (read more)A solid wooden desk at centre stage is bracketed by two more placed behind it. A whiteboard is off to one side, and a pile of broken office chairs rises on a tiered platform, suggesting a throne. The rollers from five swivel chairs hang threateningly over the actors’ heads. As the audience is seated, actors in dour business suits enter and exit, checking papers with a sense of subdued activity as the ethereal strings, pads, and pizzicato melodies of Ben Keene’s sound design float through the space. Someone Blu-Tacks a pie chart split into three on the whiteboard, foreshadowing the play’s famous conceit. These pre-show touches promise an anachronistic corporate world with overtones of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and the Time Variance Authority from Marvel’s recent Loki.

... (read more)Towards the end of the first act of Happy Days, Samuel Beckett spells out clearly the question that is at the heart of his work and that of the playwrights loosely grouped under the title ‘absurdist’. His protagonist, Winnie, buried up to her waist in earth, is describing the conversation of a couple who, wandering by, have caught sight of her. The man turns to his female companion. ‘What’s she doing? he says – What’s the idea? he says – stuck up to her diddies in the bleeding ground – coarse fellow – What does it mean? he says – What’s it meant to mean? … Do you hear me? he says – I do, she says, God help me … And you, she says, what’s the idea of you, what are you meant to mean?’

... (read more)