Fiction

Diane Armstrong should have stuck to the facts. The many surprising particulars that illuminated her two fine histories of the Jewish refugee experience (Mosaic: A Chronicle of Five Generations, 1998, and The Voyage of Their Life, 1999) have been replaced, in her first novel, by clichés and banalities that turn to soap opera her account of an Australian forensic scientist unearthing the secrets of her own past.

... (read more)In a recent feature article in the Guardian Review, William Boyd proposed a new system for the classification of short stories. He constructed seven stringently categorical descriptions and ended his article with a somewhat predictable – that is to say, canonical – list of ‘ten truly great stories’, among which were James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Spring at Fialta’ and Jorge Luis Borges’s ‘Funes the Memorious’. Most of the writers cited were male, and the classifications were confident demarcations in terms of genre and mode (‘modernist’, ‘biographical’). It is difficult to know, and no doubt presumptuous to speculate, what Boyd would make of Frank Moorhouse’s edited collection The Best Australian Stories 2004. Garnering them ‘at large’ by advertisement and word of mouth, Moorhouse received one thousand stories, from which he selected ‘intriguing and venturesome’ texts, many of which display ‘innovations’ of form. Of the twenty-seven included, six are by first-time published writers and twenty are by women. This is thus an open, heterodox and explorative volume, unlike its four predecessors in this series in reach and inclusiveness. It is also, perhaps, more uneven in quality: a few stories in this selection are rather slight; and the decision to include two stories by two of the writers may seem problematic, given the large number of submissions and the fact that the editor claims there were fifty works fine enough to warrant publication. A character in one of the stories favourably esteems the fiction of Frank Moorhouse over that of David Malouf: this too may be regarded as a partisan inclusion.

... (read more)Ugh: today I realised Colleen McCullough’s latest book (her fifteenth), Angel Puss, which ABR sent to me several weeks ago, needs to be read, reviewed and dispatched by January 3. The dust jacket précis reveals that this novel is ‘exhilarating’ and ‘takes us back to 1960 and Sydney’s Kings Cross – and the story of a young woman determined to defy convention’ ...

... (read more)What a phenomenon Bryce Courtenay is. In a world where we are constantly being told that books are on the way out, he sells them by the barrow-load. They’re big books, too. This one weighs 1.2 kilograms and is seven centimetres thick. It’s the kind of book that makes a reviewer wish she was paid ...

... (read more)‘It is in love that violent desires find the greatest satisfaction,’ wrote Stendhal in On Love (1842). Though distanced by land, sea and centuries, Sophie Cunningham’s début novel, Geography, gives contemporary testimony to the same enduring claim. Set for the most part among the suburbs and landmarks of Melbourne and Sydney during the 1990s, Geography travels back and forth in time and place between Los Angeles and Sri Lanka, establishing an expansive mise en scène for this explosive meditation on the complexities of love, sex and self-destruction.

... (read more)Day I – new suitors

The mountain thinks: Wilson, eh? Finally he comes. About time. The trucks stop on the north side where the Rongai route begins and Kilimanjaro’s powdered skirt tumbles out of Tanzania into Kenya. Her lower folds are less sensitive, but she still feels us among the thousands. In her stones she weighs our upward love and thinks: How much do you really want me? We start late and pad steadily from 1900 metres on the trail’s seamy musk with no perspective on the summit. Above us, only a shrug of fat hills and cloud. Kilimanjaro’s broad, high face (all ice-lashes and airless hauteur) is a vast four kilometres further up. Emmanuel tells us to walk polepole (slowly, gently). ‘Like walking your girlfriend home,’ he says.

... (read more)Drown Them in the Sea by Nicholas Angel & The Hanging Tree by Jillian Watkinson

Aspiring Australian writers lament the fact that few publishers are accepting unsolicited fiction manuscripts. Those that do accept them lament the fact that they are inundated by around a thousand submissions each year. What’s the solution? Increasingly, it seems, awards for unpublished work with publication as the prize. Writers know their work will at least be looked at; publishers can outsource to judges the culling of what would otherwise be their slush pile. It is no longer just the 24-year-old Vogel Award, with its promise of publication by Allen & Unwin. State-based awards now guarantee publication by UQP, FACP and Wakefield Press.

... (read more)Leavetaking by Joy Hooton & Temple of the Grail by Adriana Koulias

These two quite different historical novels, both by first-time novelists, reveal once again the many difficulties of that genre, no matter how much information the author has gathered. The publisher of Temple of the Grail has provided ample publicity material. Along with the usual media release, there is a two-page puff piece couched in the first person about how Adriana Koulias came to write and publish the book. Koulias is Brazilian by birth, from a Catholic family that moved to Australia when she was nine: ‘By the time I was eighteen I had come into contact with a cornucopia of religion and philosophy.’ Much of this lore has been fed into Temple of the Grail, which sets out, she says, ‘to show how religious zeal, carried to extremes, eventually leads to error’. In addition to this promotional material, the book itself contains a foreword by David Wansbrough praising the book to the skies:

... (read more)Seeing George by Cassandra Austin & Backwaters by Robert Engwerda

Of these three début novels, John Honey’s Paint is by far the richest: the only one that has the feel of a world turning as its pages ever more rapidly must be turned. Honey has created characters that matter to the reader and offers a truly immersive reading experience.

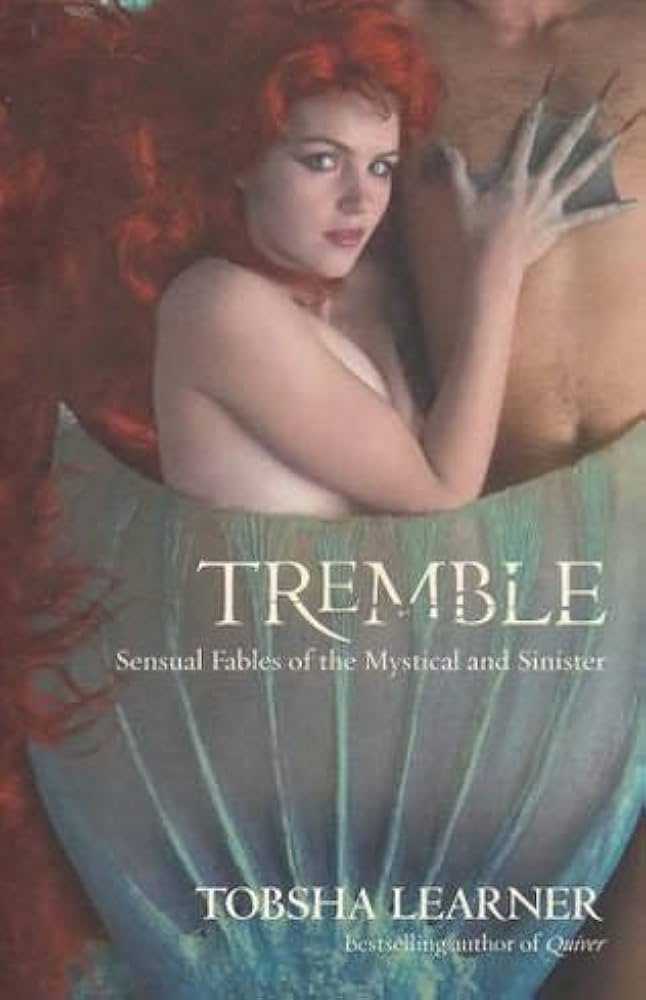

... (read more)Tremble: Sensual fables of the mystical and sinister by Tobsha Learner

Tobsha Learner, the author of three books, is best known for her collection of sexy short stories Quiver (1997), which is not to be confused with Nikki Gemmell’s Shiver (1997). Learner’s latest effort is also a compilation of sexually charged tales. Tremble, however, is more ambitious than her previous offering. Instead of assembling all her characters in one city (Sydney) and in a contemporary setting to perform naked gymnastics with one another, Learner scatters her new cast all over the globe and within various time frames. From somewhere off the Cape of Trafalgar in the early nineteenth century to a stuffy British museum in 1851, from the dustbowl of Oklahoma to a tiny Greek island, Learner’s lusty protagonists gasp and moan their way throughout the night.

... (read more)