Arts

Victorian Visions: Nineteenth-Century Art from the John Schaeffer Collection by Richard Beresford

by Christopher Menz •

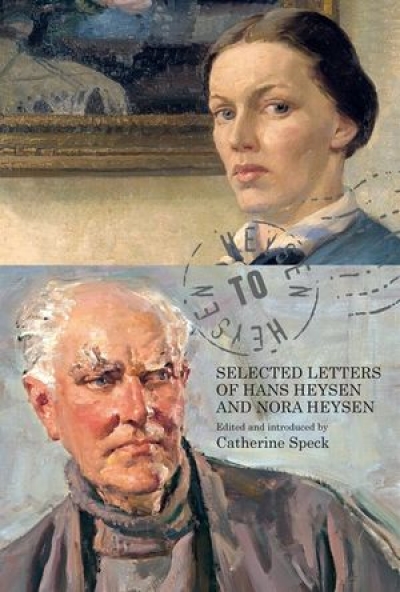

Heysen to Heysen: Selected Letters of Hans Heysen and Nora Heysen by Catherine Speck

by Christopher Menz •

Images of the Interior: Seven Central Australian Photographers by Philip Jones

by Helen Ennis •

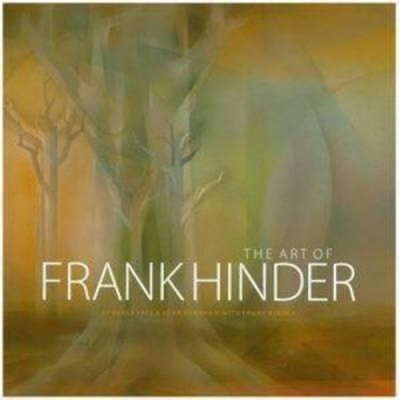

The Art of Frank Hinder by Renee Free and John Henshaw, with Frank Hinder

by Ann Stephen •

The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900 by Stephen Calloway and Lynn Federle Orr

by Alison Inglis •

Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria, 50th Edition edited by Isobel Crombie and Judith Ryan

by Jane Clark •

Paradoxical neglect

Dear Editor,

Patrick McCaughey’s article ‘NativeGrounds and Foreign Fields: The Paradoxical Neglect of Australian Art Abroad’ (June 2011) caught my attention because of its title, then its content. The ...

Vienna: Art and Design: Klimt, Schiele, Hoffmann, Loos by Christian Witt-Dörring et al.

by Andrew Montana •