Arts

The Cambridge Companion to Australian Art edited by Jaynie Anderson

by Andrew Sayers •

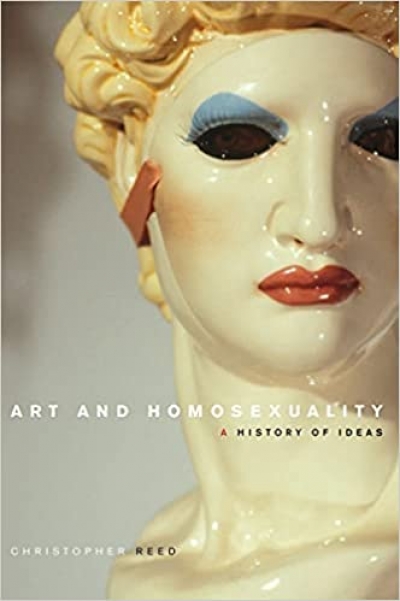

Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas by Christopher Reed

by Robert Aldrich •

Burning Issues: Fire in Art and the Social Imagination by Alan Krell

by Peter Hill •

The initial idea was for a new front door at the National Gallery of Australia. At least that is how Ron Radford, director of the Gallery, presented it to the one thousand or so guests in his remarks at the official opening of Andrew Andersons’ and PTW Architects’ Stage One ‘New Look’ at the NGA on Thursday, 30 September. Clearly, for the money involved and ...

Brett Whiteley: A sensual line 1957–67 by Kathie Sutherland

by Vivien Gaston •

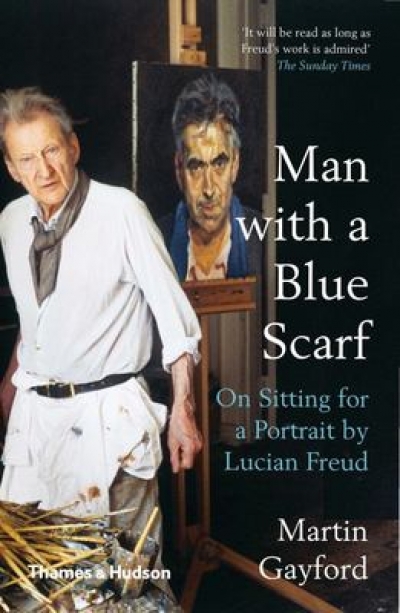

Man with a Blue Scarf: On sitting for a portrait by Martin Gayford

by Angus Trumble •

The Donald Friend Diaries: Chronicles & Confessions of an Australian Artist edited by Ian Britain (foreword by Barry Humphries)

by Patrick McCaughey •

Desert Country by Nici Cumpston with Barry Patton & Yiwarra Kuju by National Museum of Australia

by Brenda L. Croft •

There is so much beauty around us if only we could take the time to open our eyes and perceive it. And then share it. Love is the key word.

(Carol Jerrems, A Book About Australian Women)

In 1973, Carol Jerrems photographed a little girl, Caroline Slade, at her fourth birthday party in Toorak. Standing coyly with ha ...