Archive

Sign up to From the Archive and receive a new review to your inbox every Monday. Always free to read.

Recent:

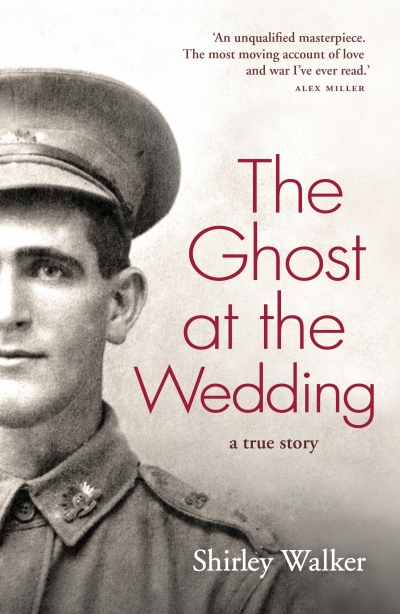

The Ghost at the Wedding: A true story by Shirley Walker

by Brenda Niall •

Why do you write?

It’s an excuse to hang around books, which is all I’ve done, one way or another, over the course of my career.

Are you a vivid dre ...

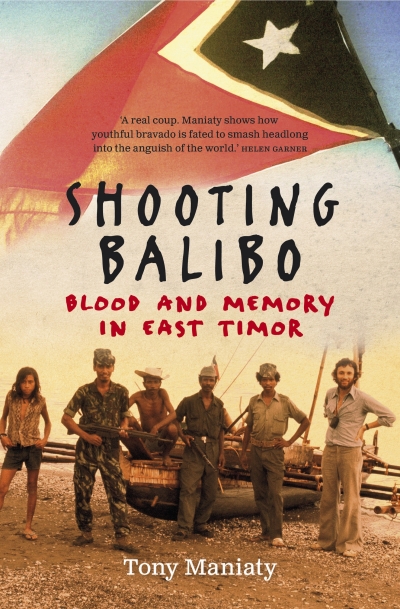

Shooting Balibo: Blood and memory in East Timor by Tony Maniaty

by Jill Jolliffe •

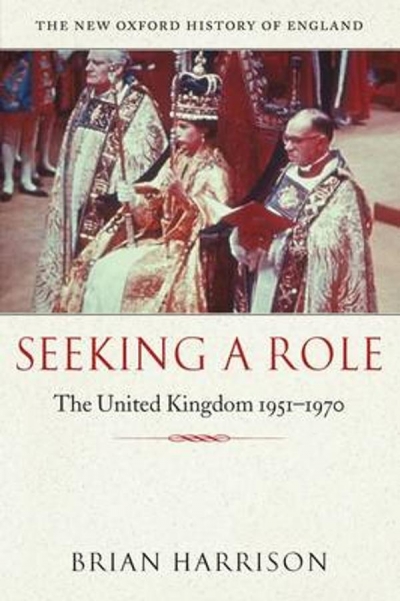

Seeking A Role: The United Kingdom 1951–1970 by Brian Harrison

by Neal Blewett •