Allen & Unwin

Fatal Attraction by Bruce Grant & How to Kill a Country by Linda Weiss, Elizabeth Thurbon and John Mathews

by Jock Given •

Well May We Say edited by Sally Warhaft & Speaking for Australia by Rod Kemp and Marion Stanton

by James Curran •

Writing Feature Stories: How to research and write newspaper and magazine articles by Matthew Ricketson

by Joel Becker •

Sybil’s Cave by Catherine Padmore & The Submerged Cathedral by Charlotte Wood

by Anna Goldsworthy •

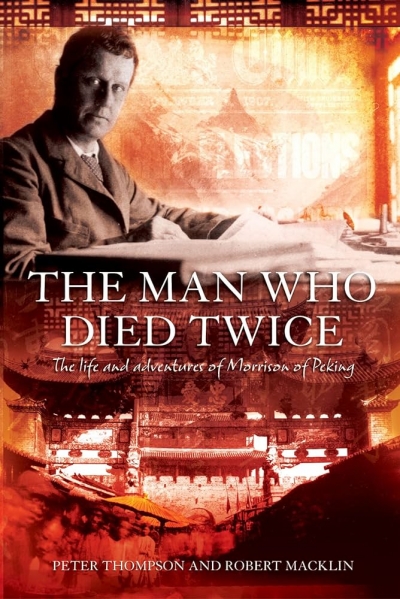

The Man Who Died Twice: The life and adventures of Morrison of Peking by Peter Thompson and Robert Macklin

by Gideon Haigh •