Australian Poetry

A couple of months ago, driving with my daughter just outside the wheat-belt town of York, Western Australia, we came across a ‘28’ parrot that had just been struck by a car. I scooped it up in a cloth, and my daughter held it on the back seat until we could get home. Having been bitten numerous times by those ‘strong and hooked’ beaks, I warned her to be wary. But the parrot – a splay of emerald, turquoise, black and yellow feathers – was too dazed to bite, and clearly had a broken wing. Though we’ve always called these beautiful birds 28s, technically they are a ring-necked parrot, and possibly even the Port Lincoln variety of ring-necked. The demarcation lines between varieties are hazy. The local ‘nickname’ matters as local names do. We eventually handed the injured bird over to the local ‘bird lady’, who later let me know that it had died due to massive brain damage. My daughter doesn’t know it died. She said it was the closest she’d ever come to something so ‘amazing’. I left it at that.

... (read more)The kookaburra begets the sacred kingfisher

who begets the rainbow bee-eater

who begets the firetailed finch

who begets the forty-spotted pardalote

who begets the damsel fly

who begets the jewelled beetle

who begets a pentangle of reflected light

that falls on a colony of dust mites

... (read more)(from Peter Henry Lepus in ‘Iraq, 2003’)

Are all Arabs Muslims? Peter Henry asks.

Nobody answers him.

She’s got dark hair that stops

just above her shoulders. Turns up at the ends.

She’s very slim, Max says.

He’s talking to Hamid

about Weasel Smith’s girlfriend,

whom he is hoping to meet

somewhere south of Baghdad.

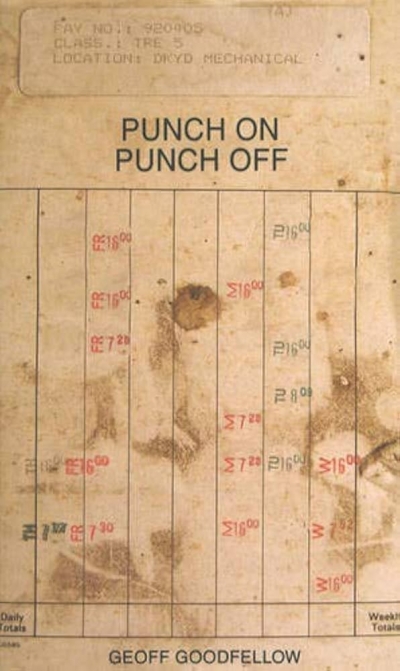

... (read more)Punch On Punch Off by Geoff Goodfellow & Fontanelle by Andrew Lansdown

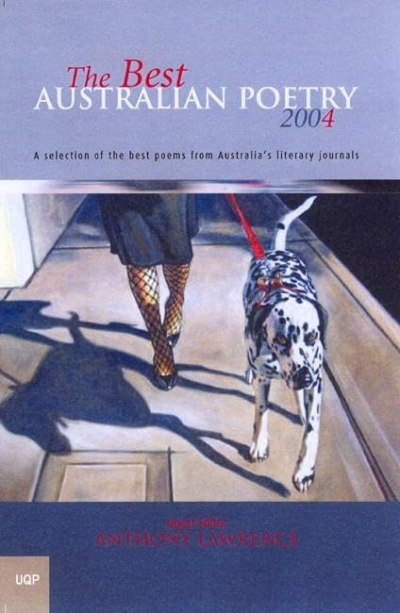

The Best Australian Poetry 2004 edited by Anthony Lawrence & The Best Australian Poems 2004 edited by Les Murray

He sang of old coins buried beneath the dunes,

to the north of the island, near the old artillery battery.

For forty years he rowed for mullet north, and south,

where the war epic motion picture was shot recently.

To the north of the island, near the old artillery battery

we played hide and seek as kids in acres of bladey-grass.

Where the war epic motion picture was shot recently

no one was allowed within a thousand metres.