Archive

So much activity outside

where sunlight spills across the snow

like cream –

Rain bubble-wrapping the windows. Rain

falling as though someone ran a blade down the spines

of fish setting those tiny backbones free. Rain

with its squinting glance, rain

The Diamond Anchor by Jennifer Mills & The China Garden by Kristina Olsson

by Kate McFadyen •

Five Bells Australian Poetry Festival (Double Issue) edited by John S. Batts et al.

by Lisa Gorton •

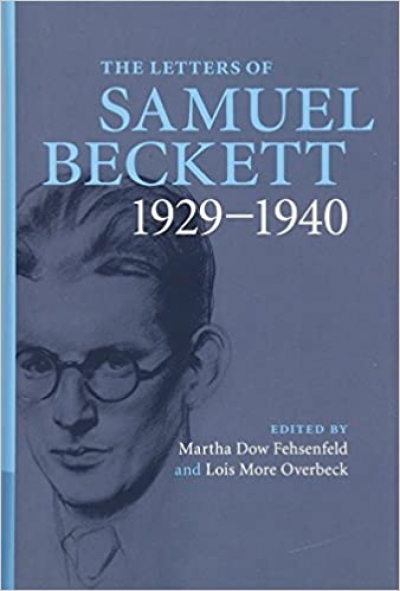

The Letters of Samuel Beckett, Vol. 1: 1929–1940 edited by Martha Dow Fehsenfeld and Lois More Overbeck

by James Ley •