War

One of the most productive and interesting areas of research in applied philosophy is concerned with moral issues around warfare. Although there had been important contributions previously, Michael Walzer’s Just and Unjust Wars (1977) was immensely influential in philosophy and well beyond its confines, reinstating ‘just war’ thinking as a mainstream intellectual position. It became, for instance, a standard text in Western military academies.

... (read more)Brenda Niall reviews 'The Ghost at the Wedding: A true story' by Shirley Walker

Some stories deserve to be told more than once. Retold, they cannot be the same. Even when the teller is the same person, the shift in time and experience will make the story new. In The Ghost at the Wedding, Shirley Walker returns to the material of her autobiography, Roundabout at Bangalow (2001), in order to focus more closely on the saddest and most powerful memories therein: those of the young men of her family who served in two world wars.

... (read more)Elisabeth Holdsworth reviews 'Captain Bullen’s War: The Vietnam War diary of Captain John Bullen' edited by Paul Ham

Too many specific years in the twentieth century were said to be ‘pivotal’, but 1968 was clearly a standout. In the United States, Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated; there were student protests in Paris; and Russian tanks signalled the end of the ‘Prague Spring’. In January 1968, on the other side of the world, in an area once known as French Indochina, the army of the National Liberation Front (the Vietcong) invaded the imperial city, Hué, and all other major cities in South Vietnam. This was the infamous Tet Offensive.

... (read more)David Horner reviews 'The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (Second Edition)' edited by Peter Dennis et al.

In his famous but tendentious 1989 essay ‘The End of History’, the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama argued that ‘we may be witnessing ... not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history’. A similar proposition might well have been made about Australian military history. By 1989 the great era of Australian military history seemed to have passed. The centrepieces of this era were the two world wars, which were so large, bloody and traumatic that they seemed destined to dominate the subject for many decades to come. What came before – the New Zealand Wars, Sudan, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Boer War – were seen as preliminary or preparatory episodes, or, as the title of one book on Sudan put it, ‘The Rehearsal’. The conflicts that followed World War II were postscripts. The performances and sacrifices of Australians in Korea, Malaya, Borneo, and Vietnam were measured against the earlier experiences of the world wars. All of Australia’s senior commanders in Vietnam had served in World War II, while most of the younger fighters there were the sons of World War II veterans.

... (read more)Riaz Hassan reviews 'Descent into Chaos: How the war against Islamic extremism is being lost in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia' by Ahmed Rashid

Two months ago, I was in Islamabad to address an international conference on suicide terrorism. The Pakistani army was engaged in heavy fighting with the Islamic militants in the Pashtun-dominated northern Pakistan, bordering Afghanistan. The security situation was deteriorating. Senior Pakistani intelligence officers were worried that it would lead to an escalation of suicide attacks. Their assessment was supported by the other government officials, including doctors working in the region, who told me of the widespread perception among Pashtuns that the predominantly Punjabi Pakistan army was committing genocide of the Pashtun nation and was thus turning the population against the army. The aerial bombings by Pakistani helicopter gunships and the US-NATO drones were causing many civilian casualties.

... (read more)Yossi Klein reviews 'Where The Streets Had A Name' by Randa Abdel-Fattah

and from every dead child a rifle with eyes,

and from every crime bullets are born

which will one day find

the bull’s eye of your hearts.

And you’ll ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

So wrote Pablo Neruda, of the Spanish Civil War (‘I’m Explaining a Few Things’, 1947). These words could apply in any place where children are made to suffer and thus to hate. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s Where the Streets Had a Name is a book whose pages resonate with these themes, unflinchingly; remarkable because hers is a book written for children and about children – those living in the West Bank.

... (read more)Lyn McCredden reviews 'View From The Lucky Hotel' by Sandy Fitts

There are traces of a constant, oscillating motion of conscience in Sandy Fitts’s poetry. References to the burden of ‘history’ pit the poems, with ‘history’ standing for everything we need to address in the present, through the power of eloquence, but also in fear that such words are not enough. From the opening, prize-winning poem, ‘Waiting for Goya’, to the closing images of ‘Blue Mop’, the act of poetry emerges and is scrutinised for what it might do in the world:

... (read more)our figures leaning toward each other

to exchange a few uncertain words

about the mop- utility- aesthetics-

In its 250 years of statehood, Afghanistan has gone through numerous episodes of political rupture. The principal causes of these upheavals have remained more or less the same: an underdeveloped economy and the inability of the rulers to shift from a tribal political culture, to a more participatory national politics based on modern and democratic national institutions and rules of governance. As a result, with rare exceptions, the rulers of Afghanistan have depended on foreign patrons and not on the human and material resources of the nation to rule. This political milieu of buying the support of tribal leaders has led to fratricidal wars of succession and pacification, with devastating consequences, resulting in extended periods of political and social unrest and lawlessness. These bloody conflicts, often called jihad by the contestants, have facilitated and even invited foreign interventions by the British, Russians, Pakistanis, Iranians, and now the Americans and their allies.

... (read more)Jay Thompson reviews ‘At Thy Call: We did not falter’ by Clive Holt

At Thy Call is Clive Holt’s account of his experience as a soldier in the Angolan War. The author aims to convey the enormity of this event and the impact it has had upon the servicemen involved. In doing this, he provides an alternative to those writings that have addressed only ‘the tactical components of the war’.

The book opens in the late 1980s, when the teenage Holt entered the conflict in Angola as part of South Africa’s compulsory two-year military conscription for white males. Holt describes the carnage and fear that he and his fellow servicemen frequently experienced. The author also discusses his struggle with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the war’s aftermath.

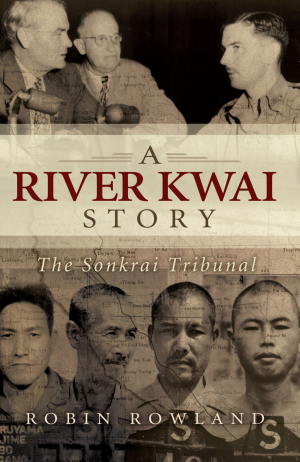

... (read more)John Connor reviews 'A River Kwai Story: The Sonkrai Tribunal' by Robin Rowland and 'The Men of the Line: Stories of the Thai–Burma railway survivors' by Pattie Wright

These two books on the building of the Thai–Burma railway in World War II are very different in format and tone. Australian film-maker Patti Wright’s Men of the Line is an exquisitely designed collection of stories and images by Australian prisoners of war who were forced to build the railway for their Japanese captors. Wright describes her book as ‘a tribute to the ex-POWs who experienced the best and worst that human nature can offer and returned to tell the tale’. Canadian journalist Robin Rowland’s A River Kwai Story: The Sonkrai Tribunal is a solidly researched investigation that concentrates on F Force, the group of Australian and British prisoners that suffered the worst death rate on the railway, and the postwar war crimes trial that found seven Japanese soldiers guilty of the ‘inhumane treatment’ of these men. Rowland concludes that the Japanese did commit war crimes; she also exposes failures by Australian and British officers that increased the POWs’ suffering.

... (read more)