Accessibility Tools

- Content scaling 100%

- Font size 100%

- Line height 100%

- Letter spacing 100%

Archive

The World of Thea Proctor by Barry Humphries, Andrew Sayers, and Sarah Engledow

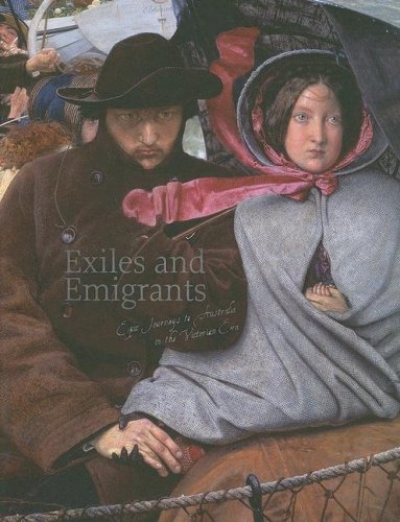

Exiles and Emigrants: Epic journeys to Australia in the Victorian era by Patricia Tryon Macdonald

Ten years ago, the venerable essay was a kind of Australian fossil, rare as compassion in a bourse. They still figured in the learned journals, but other sightings were infrequent. When the current Editor of ABR proposed the first major anthology of Australian essays to his then colleagues at OUP, it was doubtless perceived as yet another instance of his eccentricity, but when it was published in 1997 Imre Salusinszky’s Oxford Book of Australian Essays was greeted with enthusiasm. Other anthologies followed in the 1990s, including the first of the Black Inc. Best Australian Essays, a series that now runs to eight volumes. Never has the essay form been more visible, more necessary, more popular, give or take the odd skirmish. Tamas Pataki’s ‘Against Religion’, published in our February issue, is a fine example of how essays can captivate and get under people’s skin. No other essay has so polarised our readers or generated as much correspondence, ranging from a kind of epistolary sigh of relief that ‘someone has said it at last’ to indignation at Dr Pataki’s supposed temerities (see our Letters pages, and there are more to come). That’s a good thing, and ABR looks forward to presenting other views on the subject, plus a response from Dr Pataki in the April issue.

... (read more)There is no doubt that the state of writing about contemporary Australian art would be in dire straits without the support of Craftsman House. In the past two decades, this small Sydney-based publisher has plugged significant gaps in the field with some of its most influential texts: Vivien Johnson’s ground-breaking work on Australia’s Western Desert painters (1994); Charles Green’s thorough mapping of Australian art since 1970 (Peripheral Vision, 1995); and one of the first, and still most concise, English-language surveys of Soviet and early post-Soviet art, immediately spring to mind. This is not to say that all of these initiatives were limited to the thrall of academia. In collaboration with the magazine Art and Australia, Craftsman House produced a series of monographs on emerging and mid-career Australian artists at a time when their CVs generally hinged on catalogue essays or the occasional review. The effect was complementary: alongside the advocacy of artists such as Janet Laurence, H.J. Wedge and Hossein Valamanesh came the franking of a new wave of important local critics: not just Green and Johnson, but Chris McAuliffe, Paul Carter, Benjamin Genocchio and Ashley Crawford as well.

... (read more)