Accessibility Tools

- Content scaling 100%

- Font size 100%

- Line height 100%

- Letter spacing 100%

From the Editor’s Desk (17)

The Rape of Lucrece

There is at least one bravura performance in Melbourne right now, and it warranted a much larger house than we saw last week (February 1), when Southbank Theatre was only half full. The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of William Shakespeare’s long poem The Rape of Lucrece was first seen in Australia during the recent Sydney Festival, but it was premièred almost two years ago, at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

On a sharp triangular stage – mostly gloomy, sometimes lit, with tall, distressed pictures hanging on the walls – Camille O’Sullivan recites and sings most of the 1855 lines (the performance lasts eighty minutes). Irishman Feargal Murray, her sympathetic accompanist on piano, helped to adapt the poem for the stage; Elizabeth Freestone is the director.

O’Sullivan – part French, part Irish, a former architect and painter who now devotes much of her career to music – bounds onto the stage in a dark fascist overcoat and introduces the poem (rarely performed, rarely listed as one of Shakespeare’s major works) so urgently and accessibly that it takes a moment before we recognise the verse. Lucrece (1594) and the earlier Venus and Adonis (1593) were conceived as a pair (both are dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton). The Lucrece stanza has an additional rhyme (ababbcc): Venus and Adonis is ababcc.

The scene itself, unlike that of the al fresco Venus and Adonis, is claustrophobic: a tent in ‘the besieged Ardea’ of the opening line. Brilliantly, with her excellent vocal resources, O’Sullivan introduces her three characters: the cavalier Collatine, who boasts of his wife’s beauty and virtue, and rashly leaves her alone; the visiting Tarquin, who listens and resolves to have her; and Lucrece herself, ‘Lucrece the chaste’, a phrase which tells us everything until after the rape, when notions of honour and shame rouse her.

Camille O'Sullivan as Lucrece (photograph by Keith Pattison)

Camille O'Sullivan as Lucrece (photograph by Keith Pattison)

Tarquin’s lengthy approach to the tent is most suspenseful (the lighting is deft), and the rape itself generates colossal tension; rarely is an audience so attentive, so respectful. O’Sullivan – throwing off Tarquin’s brute coat and becoming the supine victim in her slip – conveys Lucrece’s terror and outrage. When she sings the verses, as she often does, O’Sullivan’s vast cabaret experience is evident; the voice is strong but flexible, and highly emotive.

Rape done, Tarquin (‘this faultful lord of Rome’), sickly sated, makes his exit:

He like a thievish dog creeps sadly thence;

She like a wearied lamb lies panting there;

He scowls and hates himself for his offence;

She, desperate, with her nails her flesh doth tear;

He faintly flies, sweating with guilty fear;

She stays, exclaiming on the direful night;

He runs and chides his vanished, loathed delight.

Lucrece – left a ‘hopeless castaway’ – summons Collatine, intent on revenge, only to stab herself on his arrival, a cue to two of the most vivid stanzas in the poem:

Stone-still, astonished with this deadly deed,

Stood Collatine and all his lordly crew;

Till Lucrece’s father that beholds her bleed,

Himself on her self-slaughtered body threw;

And from the purple fountain Brutus drew

The murderous knife and as it left the place,

Her blood, in pure revenge, held it in chase;

And bubbling from her breast, it doth divide

In two slow rivers, that the crimson blood

Circles her body in on every side,

Who like a late-sacked island vastly stood

Bare and unpeopled, in this fearful flood.

Some of her blood still pure and red remained,

And some looked black and that false Tarquin stained.

O’Sullivan – weary after this virtuoso reading and performance – is clearly moved at the end, as is the audience. No one interested in innovative theatre or Shakespeare’s poetry should miss this unforgettable performance.

The Royal Shakespeare Company production of The Rape of the Lucrece is presented at the Sumner Theatre, Melbourne Theatre Company, 6–10 February 2013.

Opera Australia's Melbourne season

Opera Australia returns to Melbourne for a short season of three operas – one German, two Italian, all notable for their gory finales.

The season opened on 14 November with Moffatt Oxenbould’s production of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, which has been entertaining us since 1998. Done well, Puccini’s ‘orientalist’ masterwork is riveting. The orchestration alone is worth the price of the ticket. Done badly, it can be interminable. The première – at La Scala, in 1904 – was a famous fiasco, a rare failure for the wizard of Italian opera.

Happily, this was an outstanding performance, one that got better and better all night, culminating in scenes of great drama and pathos. Conductor Giovanni Reggioli drew sure, subtle sounds from Orchestra Victoria. Oxenbould’s stately but dramatic conception holds up well. The courtly semaphore-like Japanese gestures are ubiquitous at first, but this settles down, allowing us to concentrate on the many dramas of fifteen-year-old Cio-Cio-San, perhaps the composer’s most poignant creation, along with Liù in Turandot. Barry Ryan, our Sharpless, the US Consul who must do Pinkerton’s dirty work, is outstanding. Young local James Egglestone plays the American cad. It is a light, high, accurate voice, and he hits all the notes, possibly waning slightly in the arduous love duet, but returning to the stage in outstanding voice an hour later (or should we say three years later?), when Pinkerton, accompanied by the American wife he always craved, acknowledges his many imperfections in the great trio and in his doleful aria ‘Addio, fiorito asil’.

James Egglestone and Hiromi Omura in Madama Butterfly

James Egglestone and Hiromi Omura in Madama Butterfly

(photograph by Jeff Busby)

Sian Pendry, as Butterfly’s constant servant Suzuki, makes much of this noble rôle, and acts affectingly. But this is Hiromi Omura’s night, and this must be one of the finest Butterflys we have seen in years. Quite an actress, she remains in character all night, negotiating with ease the heroine’s marked transformation in outlook and temperament, from clueless virgin to undeceived suicide. The fantasy scene that opens Act Three could easily come unstuck in lesser hands, but here Omura is at her most actorly and compelling. 'Un bel di' could hardly be sung better. It is not a huge voice, but Omura copes with Puccini’s surges. Only the moving farewell to her infant son (a remarkably well-behaved little actor) is sung light-voiced, but it is no less affecting for that. Really, it is an awesome assumption of a truly great and truly difficult rôle.

Hiromi Omura as Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Hiromi Omura as Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Nothing, it seems, happens in Scotland except cloudage and mariticide. Opera Australia’s new production of Lucia di Lammermoor (first presented in Sydney a few weeks ago) is remarkably sombre. A series of huge panels, covered in dark clouds, rise, fall, and tilt, providing a kind of bleak architecture for this latest rendition of Donizetti’s most famous opera.

John Doyle’s direction is sober, static, subdued. The sizeable chorus, deployed by Doyle, behaves like a frosty Presbyterian army. They enter in rows, interweave methodically, handle props as if their moral reputations depend upon it, and largely eschew expression. The wedding celebrations at Ravenswood Castle are quite joyless, despite the rousing music. D’immenso giubilo, indeed! When Lucia, having murdered her unwanted spouse, enlivens the occasion with her sanguinary fancies, the chorus remains rigid, emotionless, barely responding to Donizetti’s flitting freak. Still, the chorus sings forcefully and impressively throughout.

The vast stage is radically bare. This would suit Wagner, but I’m not sure about Donizetti’s busy, peopled opera. When two chairs are (theatrically) introduced in the third scene of Act One, it feels more portentous than the Second Coming. Later there is a long nuptial table on which the hysterical Lucia relives her gory consummation.

Lucia, of course, always dominates this opera, notwithstanding the excellence of Donizetti’s writing for male voices in this his forty-fifth opera (first performed in Naples in 1835). Famous as the long and elaborate mad scene is, Lucia has some superlative music in her earlier scenes, notably ‘Regnava nel silenzio’ and the jubilant cabaletta ‘Quando, rapita in estasi’ in the first scene, and a small, exquisite cavatina during her demoralised scene with Raimondo.

Emma Matthews as Lucia – girlish, sanguine, wide-eyed, a victim who smiles too much for her own good – is (understandably) cautious at first, and the high notes feel a little effortful, though always accurate. For the first act it is a winsome performance, not terribly original.

The mad scene is quite different. Here Matthews comes alive – comes alive to die. There is nothing glamorous about opera these days. Twitching and mad-eyed, the bare-footed Lucia shuffles on stage, her plain white nightgown covered in blood (with the usual modish menstrual additions). Here the orchestra plays every bit as well as it did during Butterfly – which augurs well for next year’s Ring Cycle. The addition of a glass harmonica-like electronic keyboard (the harmonica was Donizetti’s original choice, but Benjamin Franklin’s invention) during the mad scene is inspired. It is such a weird, luring, other-wordly sound – perfect for this long, abject, infinitely melodious scene. Matthews – eschewing grandiose effects and shuffling round the stage like a demented murderess in Prime Suspect – takes it slowly and imaginatively. She responds brilliantly to the companionable flute. Rightly, she brings down the house with the cabaletta ‘Spargi d’amaro pianto’.

Emma Matthews in Lucia di Lammermoor (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Emma Matthews in Lucia di Lammermoor (photograph by Jeff Busby)

The men are equally fine. The expressive-faced Giorgio Caoduro (Lucia’s venal brother Enrico) doesn’t waste any time and kicks off the night with a spirited aria. Aldo Di Toro, as Lucia’s hapless lover, Edgardo, is a conventional actor, but he sings his difficult music with great feeling, assurance and brio. If Opera Australia is ever going to give us another I Puritani, they need look no further than Matthews and Di Toro.

For some reason the director has chosen cut the Wolf’s Crag scene – a regrettable choice, since the music in this tempestuous contest between Enrico and Edgardo is lively and the available baritone and tenor would have savoured it. Why shorten an entertaining night at the theatre?

The youthful David Parkin, as Lucia’s chaplain Raimondo, brought impressive sympathy and accuracy to the rôle of Raimondo, Lucia’s often aghast chaplain.

(photograph by Jeff Busby)

(photograph by Jeff Busby)

In one of the many paradoxes of bel canto opera, Lucia’s mad scene doesn’t close the opera. It is Edgardo, on being told of Lucia’s mad descent, who ends it with two arias, during the second of which he manages to stab himself much more neatly than Lucy of Lammermoor could manage. As the curtain descended – or rather, as the big cloudy panels folded on the latest victim – our boisterous conductor, Guillaume Tourniare, lost control of his baton, which went sailing over the pit – a fitting flourish.

Unfortunately, New York and the Met call and I will miss Cheryl Barker (who sang so beautifully in the Sydney production of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt in July) in Strauss’s coruscating Salome, which opens on 1 December.

Opera Australia is performing in the State Theatre at the Arts Centre Melbourne. Madama Butterfly runs until 14 December 2012 and Lucia di Lammermoor until 15 December 2012. Salome opens on 1 December and runs until 15 December 2012.

Open letter concerning Fairfax

There is, understandably, much umbrage and anxiety in Canberra following Fairfax’s decision to remove its literary editor at the Canberra Times and to rely exclusively on literary reviews and commentaries emanating from Fairfax’s two main broadsheets, The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald – broadsheets that will themselves become tabloids next year, presumably with less literary and cultural content. Australian Book Review regrets this decision, and hopes it will be reconsidered. The Canberra Times has long carried some of the most distinctive and extensive books pages in the country. It seems extraordinary that such a wealthy city – a major university city – a national capital even – cannot support its own bespoke literary pages and must, like some outpost, rely on the word from Melbourne or Sydney. Variety of opinion and sensibility in such a deplorably concentrated media environment as ours is surely worth defending. Without it there will be many victims: writers, readers, critics, booksellers, publishers, etc. We support the campaign to overturn this unfortunate and philistine economy.

Below we carry an open letter from many of those involved in this campaign. We will update it regularly as more names are added, and we welcome readers’ comments.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

Dear Editor,

We, the undersigned, wish to draw to national attention the implication of the upcoming Fairfax consolidation of The Age, Sydney Morning Herald, and the Canberra Times book sections. This has the potential to reduce significantly the content of the three separate sections in terms of both the number of books covered and reviewers. The same review would appear in all three outlets. This will particularly impact on the Canberra Times, currently one of the best book review sections in the country, if, as seems likely, most of the reviews in future will be sourced from ‘Fairfax Central’.

This consolidation will considerably reduce divergent voice and opinion on both fiction, non-fiction, and poetry books in Australia. While Fairfax has indicated that some ‘local content’ will still be included, there is no doubt that many authors and their books will no longer be reviewed. Unlike the United Kingdom and America, where there are numerous publications, Australia is not well served by alternative national literary outlets, Australian Book Review being an honourable exception.

Canberra has the highest book purchasing and reading per head of population in the country, so it seems counter-productive that a search of the Canberra Times book section already only brings up reviews sourced from Sydney and Melbourne. We recognise the challenges confronting the newspaper industry, but we also want to emphasise that the digital era provides opportunities which are currently not being recognised in local content, advertising, and bookshop sales.

We would argue that the reading publics of Canberra, Melbourne, and Sydney are sufficiently different that online literary diversity should be promoted by Fairfax, rather than the opposite trend. The lack of public dialogue within the Fairfax papers on this issue to date, despite numerous submissions, is also a matter of regret, especially given the need for public debate is so often espoused by those organs.

Jaki Arthur, Joel Becker, Carmel Bird, Alison Broinowski, David Brooks, Sally Burdon, Alexa Burnell, John Byron, Tracey Cheetham, John Clanchy, Paul Cliff, Kirstin Corcoran, Sara Dowse, Suzanne Edgar, Christine Farmer, Heath Farnsworth, Jane Finemore, Ian Fraser, Brendan Fredericks, Irma Gold, Alan Gould, James Grieve, Janet Grundy, Robert Grundy, Marion Halligan, Paul Hetherington, Chris von Hinckeldey, Claudia Hyles, Subhash Jaireth, Brian Johns, John Kerin, Cora Kipling, Kathy Kituai, Alisa Krasnostein, Elizabeth Lawson, Lesley Lebkowicz, Caroline Le Couteur, Charlie Massy, Andrew McDonald, Debbie McInnes, Patti Miller, Jennifer Moran, Ann Moyal, Kerrie Nelson, Hoang Nguyen, Susan Nicholls, Jane Novak, Benython Oldfield, Kate O’Reilly, Frank O’Shea, Moya Pacey, Geoff Page, Andy Palmer, Bettina Richter, Andrew Schuller, David Skinner, Melinda Smith, Linda Spinaze, Peter Stanley, Colin Steele, Jen Stokes, Dallas Stow, Faye Sutherland, Peter Tinslay, Bethia Thomas, Leon Trainor, June Verrier, Kaaron Warren, Judith White, Robert Willson, Belinda Weaver, and Cameron Woodhead

Remembering Peter Steele

Bricks, knowledge, gravity

‘I just read a history of bricks.’

We learn about the ways our teachers have influenced us over many years. As an undergraduate student at the University of Melbourne, I took every class taught by Professor Peter Steele SJ. More than a decade after I first sat in his office, and only days after his death, I recall a statement he made almost as an aside during one lecture. The class was on travel writing. Not the popular genre, where narratives of Tuscan revelations or adventures on the trans-Siberian railway abound, but a more ragtag bundle of texts: The Odyssey, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, and, a particular favourite of Steele’s, Gulliver’s Travels. He wrote his doctoral thesis on Jonathan Swift, a fellow priest with an appetite for the world’s many wonders.

The reading list for Steele’s class was already an odd selection, but his casual statement in class that he had been reading about bricks revealed a world of reading that lay before me. A lover of fiction and poetry, I had devoted almost all my reading to these genres, dipping liberally into the literary essay along the way. But here was a radically different suggestion: a history of bricks; essentially a history of the buildings we construct that are meant to last. I thought of the different character of homes made of red brick, and those made of yellow brick. I pondered again the Yellow Brick Road of Oz. Later, when reading of Timbuktu’s mud architecture, and when visiting adobe pueblo sites in the American Southwest, I thought again of this history of bricks. How like the Peter Steele I came to know over a number of years to understand the world from the perspective of the materials with which we build it. In various library catalogues, I have looked up the subject of bricks, and a number of books have come up. I have often wondered which volume he read, and am sorry I never asked him. I am grateful, however, that he introduced me to the work of, among many others, Mandeville. The weird account of this knight’s travels eastward into an increasingly wild and unrecognisable medieval world is one I have returned to often, both in imagination and on the page.

Another text Steele revealed to me was the poem ‘Matthew XXV: 30’ by Jorge Luis Borges. He often brought a poem to class, projecting it on a transparency, and talked us through the reasons why the poem impressed him. Borges’ poem ends with the following lines:

… In vain have oceans been squandered on you,

in vain the sun, wonderfully seen through Whitman’s eyes.

You have used up the years and they have used up you,

and still, and still, you have not written the poem.

These final four lines, he said, never failed to humble him, to haunt him – and they have come to have the same place in my own life. I read those lines and reflect that every poem I have written fails, somewhere – is still not the poem; will probably never be that poem. Yet when I read last year’s Best Australian Poems, I was struck by Steele’s poem ‘The Knowledge’. In its gentle gathering of worldly phenomena and its almost serenely contemplative mood, I felt that this poem distilled so much of what I loved about him as a poet. I read it and thought: ‘He has written the poem’ – that is, the poem that, for me, most simply represented his poetic voice and concerns. Ever questioning that knowledge which was his life’s quest, the poem ends ‘No end of wisdom: but what does a frog / in a well know of the waiting ocean?’ The ocean had not been squandered. I wrote him a letter to tell him how much I admired the poem.

I remember, too, the day he told me of his diagnosis, now several years ago. It was before I moved to the United States to study at Georgetown, a move I may not have made if I had not been Steele’s student. I already knew he was sick, and wanted to see how he was feeling. When I arrived at Newman College he was waiting outside the gates. In a nearby café he told me frankly and clinically of how his illness had been discovered.

As ever, he was interested in talk of other things. I told him that Susan Stewart’s book Columbarium, which I had just read, contained four words that were new to me. Looking them up, I was pleased that Stewart had – of course – used them correctly, and thus taught me, better than the dictionary, how they should be used. This seemed to amuse him. We spoke of Elizabeth Bishop, and I said casually, ‘Bless her heart.’ He paused, and then with both amusement and gravity, then finally his priestly gentleness, agreed, ‘Yes. Bless her heart.’ I told him that I had recently taken up trapeze lessons. He told me, ‘I often think of you as gravity defying.’

Remembering that last statement, and a number of other things he told me over the years, I feel that, perhaps, I have not defied gravity enough; nonetheless, I like to think that Peter would be pleased to see how my interests have broadened and broadened over time, and that each time I deviate from the literature area of a bookstore or library to another set of shelves – science, history, theology, philosophy – it is not a little because of him. I am certain I am just one of the many students to whom Peter Steele delivered a much richer vision of the world.

Kate Middleton’s first collection Fire Season was published by Giramondo in 2009, and won the Western Australian Premier’s Award for Poetry. She holds an MA in literature from Georgetown University and an MFA in Poetry from the University of Michigan. From 2011–12 she is the inaugural Sydney City Poet.

Below we reproduce Peter Steele’s late poem ‘Maze’, which appeared in our June 2012 issue:

Maze

Birds are amazing, newspapers, stoves, friends.

James Richardson

But wait, there’s more – as when the hummingbird

flies backwards for the hell of it, or

the odd flamingo’s pinkened up by snacking

on blue-green algae. Aeschylus, potted

by a dropped tortoise, was one unlucky Greek –

from the same stable as Melvin Purvis,

who pioneered belching on national radio.Were you an ant you’d start the day by stretching,

and, at a pinch, have a big yawn;

were you a cricket you’d listen through the slits

of your eager forelegs: were you, alas,

a white shark, you’d never take sick but always

be hungry: and if a caterpillar,

you’d boast to the end a couple of thousand muscles.The ermine in white is the weasel in brown, and the chow

the only dog with a black tongue:

mice were sacred to Apollo: a camel-hair

may be a squirrel’s tail: the mosquito’s

wings are thrashing a thousand times a second.

If you look for the only crying creature –

or laughing come to that – consult a mirrorand find, your mind bested by wonder, your eyes

lit up again at the starry torch,

rue and its makings, something of jubilee,

the shot-silk of the hours. Better,

as the man said, to keep on dreaming small,

than see given to dissipation

the friends, the stoves, the newspapers, the birds.

Peter Steele

Australian Book Review goes to Brisbane

As we broaden our team of contributors and extend our non-Victorian content, we are currently focusing on Queensland, with good results and some excellent new contacts. We expect this quota to increase markedly in coming months. In mid-July I will be spending a few days in Brisbane, spreading the word about the magazine and recruiting new contributors. I’ll be taking part in a few events at the University of Queensland and the Queensland Writers Centre.

On Thursday, 19 July I will take part in an event at the Queensland Writers Centre – ‘an intimate evening of wine, cheese and chats’. I very much look forward to meeting Brisbane’s pool of talented and emerging writers. My aim will be to give them practical information about how they can engage with ABR and the best way to do so.

Date Thursday 19July

Time 6:00–7:30 pm

Where Queensland Writers Centre, Level 2, State Library of Queensland, Stanley Place, Cultural Centre, South Brisbane 4101

RSVP This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

As ever, I welcome approaches from seasoned reviewers or from those who want to chance their arm in a critical sense. All you have to do is send me an email outlining your experience and interests (authors, genres, etc.) and sending me one or two examples of your work. My email address: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

From time to time I chat to Sky Kirkham on the excellent 4ZzZ Book Club, our subject being literary news and recent developments and offerings at ABR. Here is a podcast of our latest conversation (courtesy of 4ZzZ Book Club). Click the Play button to stream the podcast, or click the link ('peter_rose_interview.mp3') to download it.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

Dial M for a horror story

‘An important book’ is one of those facile terms that usually have an off-putting effect – like ‘the defining election of our time’. But some publications do have a galvanising effect, and one of them is Dial M for Murdoch, written by Tom Watson and Martin Hickman, and published (with laudable speed) by Allen Lane. For this reader – this anxious addict of the print media – it’s one of the most troubling books of the year; essential reading for anyone interested in the media or in our democratic processes. It’s a perfect companion to the Guardian’s brilliant, valiant coverage of this lamentable affair.

Tom Watson, of course, is by now very familiar to us. The Labour MP – no friend of News International (‘the tub of lard’ they dubbed him sweetly) – traces the origins of the scandal, right back to 2005, when an innocuous news story about a prince’s knee injury led to something rather bigger and darker. Watson, with a few courageous, relentless colleagues – lawyers, parliamentarians, journalists, actors, some of them sick of being traduced in Murdoch’s papers and indignant at being stalked or having their phones hacked – pursued the story for years, often at some professional risk and without much support, until the revelations in July 2011 about News of the World’s conduct after the murder of Milly Dowler accelerated the process of exposing the institutionalised criminality, mendacity, corporate megalomania, and sheer immorality.

Watson and Hickman’s book is quite chilling. Peter Wilby, reviewing it in the Guardian Weekly (18 May 2012), began:

Even if you are familiar with the News of the World phone-hacking saga, you will be gobsmacked by this account. It is a tale of stupidity, incompetence, fear, intimidation, lying, downright wickedness and corruption in high places.

Robert Manne, covering the story in the June issue of The Monthly, mused about the likely coverage of the book in Australia, where Murdoch controls seventy per cent of our newspapers. Well, the book is in reliable hands at ABR. Anne Chisholm – journalist and biographer – will review Dial M for Murdoch for us. Anne is very accustomed to writing about dubious and domineering media moguls. With her late husband Michael Davie (a former editor of The Age), she wrote a biography of Lord Beaverbrook (1992).

Look out for Anne Chisholm’s review in the July–August issue and earlier in ABR Online Edition, where major articles of this kind now appear in the weeks leading up to publication.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

Patrick White – ‘Edges slightly rubbed’

While the Brits prepare to traipse up and down The Mall brandishing their Union Jacks and Coronation Chicken to fête our remote head of state’s Diamond Jubilee, what better way to mark a rather more momentous local milestone – the centenary of Patrick White’s birthday (28 May 2012) – than by reading the man again, and reading one’s favourite book by him, after more years than one cares to recall.

A few weeks back I headed to Clunes Booktown with thousands of other readers and bibliophiles. Away from the dozens and dozens of antiquarian book displays and the brass band in the quaint rotunda and the ferocious Punch and Judy and the hay-bale maze in the main street, Tess Brady and her colleagues presented an interesting program of interviews, panels, and workshops. I chaired one of these sessions, a tribute to Patrick White, and was joined by three friends and colleagues: Peter Goldsworthy, Michael Heyward, and Nicholas Jose. We began by discussing our first encounters with White. Peter Goldsworthy, borrowing The Tree of Man from the Glenelg library, thought White was from South Africa. For Michael Heyward, it was The Aunt’s Story. ‘It changed the shape of your mind.’

That’s exactly how I felt when I read White for the first time. This was earlier, in 1973, when I was seventeen. I bought a copy of The Aunt’s Story for about a dollar and read Part One in a single gulp. I don’t think I’d ever been so stirred by anything in my life, especially that last, inexpressibly tragic paragraph:

Theodora looked down through the distances that separate, even in love. If I could put out my hand, she said, but I cannot. And already the moment, the moments, the disappearing afternoon, had increased the distance that separates. There is no lifeline to other lives. I shall go, said Theodora. I have already gone. The simplicity of what ultimately happens hollowed her out. She was part of a surprising world in which hands, for reasons no longer obvious, had put tables and chairs.

I recall having to put the novel aside for a couple of weeks before I could read the other two parts. I couldn’t bear much more of that knowledge.

To be sure, Theodora’s domestic metaphysics or epistemology are guaranteed to speak to a moody adolescent, but the beauty of the prose and its rare simplicity (‘the moment, the moments, the disappearing afternoon’; and this of Theodora: ‘She was as negative as air’) move me still as I read a rather more expensive copy of the second edition (1958), which I bought recently from Kay Craddock: ‘corners of boards slightly bruised, edges slightly rubbed ... From the library of Australian journalist and critic, Neil Jillett with his bookplate, designed by Spooner ...’

Never, for me, was White’s prose more expressive, more original, more observant. I had forgotten how much energy he derives from his verbs, often of the simplest. ‘And the cows wound into the yard at evening to be milked. And Gertie Stepper punched the dough.’

It’s prose that deserves to be read aloud, slowly and savourly. In Clunes, during our panel, Nick Jose wished we could step back and just read from The Tree of Man. There’s a thought for the next Booktown. ABR might do something similar ourselves when we move to The Boyd next month.

It was salutary to be reminded in Clunes that only 464 copies of The Tree of Man have sold this century. Let us hope that Peter Goldsworthy, who came up with this dismal statistic, was responsible for a few more sales when he extolled, and briefly read from, White’s 1955 novel, for many people his greatest achievement.

Well, now we all have many reasons to reflect on and explore this uniquely gifted Australian novelist. There has been much coverage of his life and oeuvre in the press. The ABC has produced a short, interesting documentary on the man, replete with fascinating photographs and footage. At ABR we’ve been pleased to publish Peter Conrad’s review of the posthumous (and incomplete) The Hanging Garden (April issue) and David Marr’s article about White’s intermittently abortive career in the theatre (May issue). Now comes the welcome news that Text Publishing will reissue White’s first (and long suppressed) novel, Happy Valley. Copies are scarce, and very expensive. I’ve never read it, and can’t wait to do so. Text will publish it in September, with an introduction by Peter Craven (who is said to be writing a full-length book on White for Penguin).

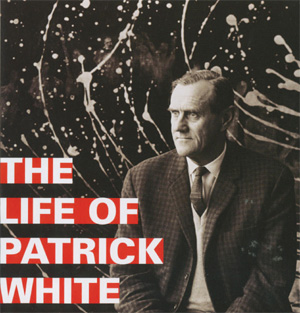

Barbara Mobbs – White’s long-time agent and friend – speaking at the opening of the National Library’s The Life of Patrick White exhibition (which is on display there until 8 July), wondered if her famous client would emerge from the twenty-year quiescence that often follows the death of a writer, however celebrated. It’s hard to imagine – deplorable to imagine – that such a voice, such a prodigious talent, will cease to be relished by readers of all ages and types for decades to come.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

Australian Book Review Online Edition

While the magazine (due tomorrow) is being printed, the May issue is now available to Australian Book Review Online Edition subscribers. After spending the past few days uploading this month’s ABR (with highlights including David Marr on Patrick White in Adelaide, and a review of Susan Swingler’s sensational family memoir on the Jolleys), I will be grateful to swap the pixels for ink and get back to some good old head-down reading. But I encourage all ABR readers to explore the Online Edition. Print subscribers can add-on a year’s subscription for just $20. An online-only subscription costs $40.

While the magazine (due tomorrow) is being printed, the May issue is now available to Australian Book Review Online Edition subscribers. After spending the past few days uploading this month’s ABR (with highlights including David Marr on Patrick White in Adelaide, and a review of Susan Swingler’s sensational family memoir on the Jolleys), I will be grateful to swap the pixels for ink and get back to some good old head-down reading. But I encourage all ABR readers to explore the Online Edition. Print subscribers can add-on a year’s subscription for just $20. An online-only subscription costs $40.

Much consideration has gone into the best way to publish Australian Book Review online. The format of ABR Online Edition means that it can be read on anything connected to the Internet, whether it be a computer, tablet, smartphone, your fridge, augmented reality glasses, whatever. This way, access to the magazine is not limited by the need for certain software or an app that is only available on one operating system. Schools, public libraries, and universities can sign up, giving thousands of users simultaneous access.

ABR Online Edition has all of the content of the print magazine, including images, Advances, Letters to the Editor, and Open Page. It is searchable, enabled with comments, and links the reader to articles on similar subjects and those by the same author. One chief advantage of subscribing is gaining access to ABR’s online backlist, which extends to November 2010. Adding to this backlist is one of our priorities, and along with this blog, the magazine is set to publish more content online than ever. Readers who are yet to subscribe can see an example of an article (Brian McFarlane’s review of The Deep Blue Sea). The whole May issue is now online.

Milly Main

Australian Book Review Ian Potter Foundation Editorial Intern

Patrick White in Canberra

To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White.

To Canberra on 12 April for the opening of a new travelling exhibition, The Life of Patrick White.

First, though, a quick dash that morning to Sydney for a meeting with Bernadette Brennan and Hilary McPhee. The three of us have been judging this year’s National Biography Award. We met in the small but spectacular Shakespeare Room at the Mitchell Library. First we shortlisted six of the dozen hitherto longlisted titles – biographies, autobiographies, memoirs. Then, after an unElizabethan lunch of shaslicks and chicken wraps, we chose our winner, who will be named and fêted and enriched by $25,000 at a ceremony on Monday, 14 May.

Then, rather glad to be able to read something other than biography for the first time in two months, I flew to Canberra rereading Persuasion for the first time in years.

The National Library’s congenial downstairs theatre soon filled, and James Spigelman (Chair of the National Library) – with a pleasing lack of ceremony (rare in the national capital; in any capital, for that matter) – introduced our two speakers.

Barbara Mobbs – Patrick White’s long-time literary agent, and now his literary executor – rightly came first. But for her the National Library and the State Library of New South Wales (partners in this venture) would struggle to mount a major exhibition, because of the paucity of manuscripts and memorabilia. Mobbs’s remarkable and laudable decision to ignore White’s express wish that all of his surviving notebooks and manuscripts (including the unfinished The Hanging Garden, which Peter Conrad reviews in our April issue) should be destroyed led ultimately – almost two decades after his death in 1990 – to their being transferred the most appropriate cultural repository in the country – the National Library of Australia.

When Mr Spigelman referred to this agential refusal – to coin a term – there was lengthy applause. Mobbs, always direct and impressively dry, began her short, witty, stylish speech in Piafian style – ‘I have no regrets.’ In passing James Spigelman had described Patrick White as curmudgeonly, but Mobbs was having none of this. She spoke of White’s kindness, good humour, and immense loyalty to friends – and to the several charities he quietly supported. She said that she enjoys writing cheques to the four principal beneficiaries of White’s estate, including the Smith Family and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Her account of White’s ignorance of technology made me feel like less of a luddite. Once, having heard of the miracle of faxing, he asked Mobbs to send a letter to London. He was bamboozled next time they met when she returned the letter. But he’d asked her to fax it! She reminisced about their shopping expeditions, when she was often mistaken for his daughter.

Mobbs recalled White’s famous penchant for the telephone. When he asked her to become his literary executor, she said it wouldn’t be very different from her previous role – except that she wouldn’t be on the phone to him for six hours a week.

Then came Judy Davis – whose role as Dorothy in Fred Schepisi’s The Eye of the Storm rightly won her another AFI award, or an AACTA, as they are now called. Extemporising freely, with funny sawing gestures, she reminded us of her inspired Judy Garland in the miniseries that won her an Emmy. Davis first read White as an eighteen-year-old, in Perth. This was in 1973, soon after he had won the Nobel Prize. The book was Riders in the Chariot – a transformative experience for her. (Here I recalled my own introduction to White that same year – The Aunt’s Story in my case: so astonishing and transcendent in Part One that I had to put it aside and compose myself for a while before resuming it.) Davis was awed by the book – ‘Suddenly I didn’t feel alone.’

Afterwards, there was time only for a quick look at the exhibition, which remains in Canberra until June before moving on to the State Library of New South Wales on 13 August. It is a large, detailed, funny, poignant exhibition. I was impressed by the letters, the manuscripts, the photographs, the dust jackets – less so by the several pictures White donated to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The desk is there (a replica of the one Francis Bacon made for him in London); above it Ian Fairweather’s Gethsemane, which he donated to in 1974 (AGNSW, not uncontroversially, sold it two years ago to help fund its acquisition of Fairweather’s The Last Supper). Among the memorabilia are his typewriter and beret and spectacles – and a certain medal, in its own case.

Later the National Library hosted a dinner at Water’s Edge. I drew a good table, with Wendy Whiteley and actors Kate Fitzpatrick and Angela Punch McGregor – and we had an immoderately good time. Kate and the Whiteleys look to be having a similarly good one with Patrick White and Manoly Lascaris in the 1980 photograph by William Yang that hangs in this highly recommended exhibition.

Peter Rose

Editor, Australian Book Review

Championing the future – patronage at ABR

Although private patronage and the arts have been linked for centuries, cultural philanthropy has not typically been associated with literature in the same way that it is with art galleries, libraries, museums, and performing arts companies. But this is changing. Since we launched our Patrons Program in 2007, we’ve been delighted by the diversity, enthusiasm, and loyalty of our generous supporters. At the end of 2007 we had eleven founding Patrons. We now have well over one hundred, and the list of Patrons occupies two pages in each issue of the magazine. We are regularly contacted by new and renewing Patrons and donors who believe in actively supporting Australian literary culture.

Although private patronage and the arts have been linked for centuries, cultural philanthropy has not typically been associated with literature in the same way that it is with art galleries, libraries, museums, and performing arts companies. But this is changing. Since we launched our Patrons Program in 2007, we’ve been delighted by the diversity, enthusiasm, and loyalty of our generous supporters. At the end of 2007 we had eleven founding Patrons. We now have well over one hundred, and the list of Patrons occupies two pages in each issue of the magazine. We are regularly contacted by new and renewing Patrons and donors who believe in actively supporting Australian literary culture.

By donating to the magazine, our supporters are not only championing Australian Book Review, but also the cause of Australian literature. Every contribution, large or small, has a genuine impact. Those who donate to ABR are helping us to encourage new writers with poetry, essay, and short story competitions; to develop our Fellowships program; to publish more fine new writing in the magazine; to protect and promote Australia’s literary heritage; and to initiate public awareness and debate about literature and ideas throughout Australia. Patrons make a tangible contribution to this vibrant agency of literary ideals.

Without the generosity of our Patrons and donors, many of the popular and diverse programs run by ABR would simply not be possible. Thanks to their donations, we have been able to expand the magazine’s programs and to support Australian writing through Patrons’ Fellowships, lucrative prizes such as the ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize, and the development of ABR Online Edition. Last year – our fiftieth birthday year – was an auspicious one for ABR. Now we look forward to introducing major new programs and features, including a range of eBooks and other online initiatives.

We always enjoy meeting our Patrons, and throughout the year we host of range of events, with noted speakers such as Alex Miller and Patrick McCaughey.

We always enjoy meeting our Patrons, and throughout the year we host of range of events, with noted speakers such as Alex Miller and Patrick McCaughey.

ABR welcomes all suggestions and enquiries about our philanthropy program. If you would like to become an ABR Patron, or if you would like to discuss ABR’s philanthropy program, call us on (03) 9429 6700 or contact me via This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Amy Baillieu

Philanthropy Manager, Australian Book Review