Archive

Was Your Dad A Russian Spy?: The personal story of the Combe/Ivanov Affair by David Combe’s wife by Meena Blesing

by Bronwen Levy •

Henry Handel Richardson and Her Fiction by Dorothy Green

by Anne Diamond •

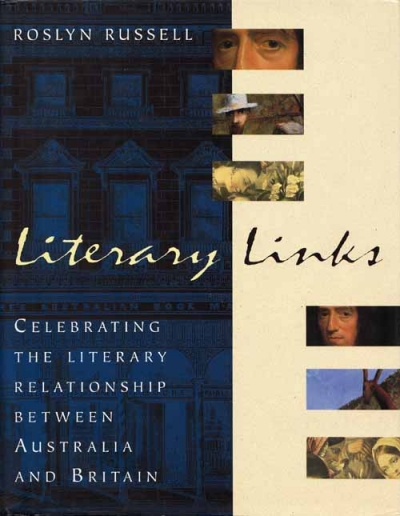

Literary Links: Celebrating the literary relationship between Australia and Britain by Roslyn Russell

by Brian Matthews •

Greg Matthews: The Spirit of Modern Cricket by Roland Fishman

by Barry Andrews •

George Johnston by Garry Kinnane & A Foreign Wife by Gillian Bouras

by Patrick Morgan •

The Delinquents by Criena Rohan & Down by the Dockside by Criena Rohan

by Christina Thompson •