Art History

Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century edited by Angus Trumble and Andrea Wolk Rager

by Anne Gray •

Crossing Cultures: Conflict, migration and convergence. The proceedings of the 32nd International Congress of the History of Art edited by Jaynie Anderson

by Patrick McCaughey •

The Art of Australia, Volume 1: Exploration to Federation by John McDonald

by David Hansen •

Centre of the Periphery: Three European art historians in Melbourne by Sheridan Palmer

by Patrick McCaughey •

A Remarkable Friendship: Vincent Van Gogh and John Peter Russell by Ann Galbally

by Fiona Gruber •

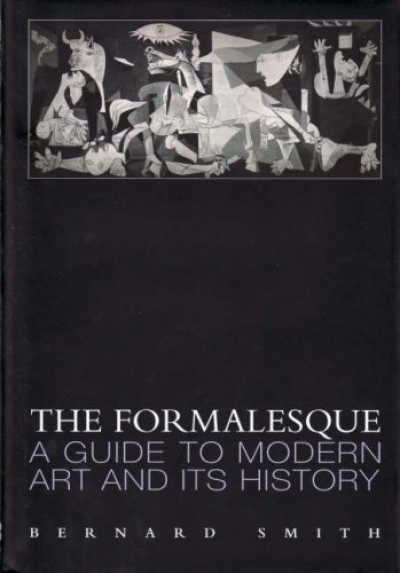

The Formalesque: A guide to Modern Art and its History by Bernard Smith

by Luke Morgan •

Turner to Monet: The triumph of landscape painting edited by Christine Dixon

by Mary Eagle •

Unstill Life by Judith Pugh & Self-Portrait of the Artist’s Wife by Irena Sibley

by Vivien Gaston •