James Ley

This week on The ABR Podcast James Ley reviews Intermezzo by Sally Rooney. For Ley, it is her most ambitious novel to date. James Ley is an essayist and literary critic. Listen to James Ley with ‘“Futile rage at nothing”: Sally Rooney’s most ambitious work to date’, published in the December issue of ABR.

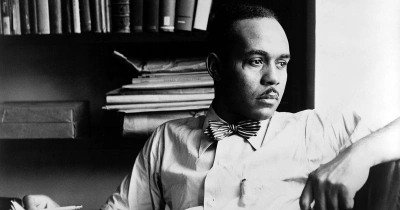

... (read more)Ralph Ellison could be abrasive. His biographer Arnold Rampersad records that James Baldwin thought Ellison ‘the angriest man he knew’. Shirley Hazzard observed that when Ellison was drinking he ‘could become obnoxious very quickly’. His friend Albert Murray recognised something in him that was ‘potentially violent, very violent. He was ready to take on people and use whatever street corner language they understood. He was ready to fight, to come to blows. You really didn’t want to mess with Ralph Ellison.’

... (read more)What the authors of these three wildly different books share is a gift for creating through language a kind of intimacy of presence, as though they were in the room with you. Emily Wilson’s much-awaited translation of The Iliad (W.W. Norton & Company) is a gorgeous, hefty hardback with substantial authorial commentary that manages to be both scholarly and engaging. The poem is translated into effortless-looking blank verse that reads like music. The Running Grave (Sphere) by Robert Galbraith (aka J.K. Rowling), the seventh novel in the Cormoran Strike crime series and one of the best so far, features Rowling’s gift for the creation of memorable characters and a cracking plot about a toxic religious cult. Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional (Allen & Unwin, reviewed in this issue of ABR) lingers in the reader’s mind, with the haunting grammar of its title, the restrained artistry of its structure, and the elusive way that it explores modes of memory, grief, and regret.

... (read more)On this week’s ABR podcast, critic and essayist James Ley reflects on J.M. Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K, forty years after its publication. Coetzee’s fourth and Booker Prize-winning novel was his landmark work, explains Ley. This was despite it receiving criticism for supposedly eliding the political realities of Apartheid South Africa by being set in ‘the realm of allegory’. Listen to James Ley with ‘An obscure prodigy: J.M. Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K at forty’, published in the August issue of ABR.

... (read more)‘Why should I be expected to rise above my times? Is it my doing that my times have been so shameful? Why should it be left to me, old and sick and full of pain, to lift myself out of this pit of disgrace?

... (read more)What’s your point?

Dear Editor,

John Carmody, in the June issue, writes a letter loaded with tendentious and pejorative language to accuse me of thundering and provocation in my review of Richard J. Lane’s Fifty Key Literary Theorists (March 2007). Carmody portrays me as self-satisfied in the same breath as he refers to his own wryness. He advises me to use words more ‘clearly and carefully’, and then composes a sentence in which ‘eliding’ creates a ‘mélange’. He charges me with portentousness in a letter that consists almost entirely of windy rhetorical questions. I have only one question: what is his point?

... (read more)