Reference

The Adelaide Art Scene by Margot Osborne & AGSA 500 edited by Rhana Devenport

by Patrick Flanery •

Stunned Mullets and Two-pot Screamers: A dictionary of Australian colloquialisms, Fifth Edition by G.A. Wilkes

by Chris Wallace-Crabbe •

The Big Picture: Diary of a nation edited by Max Prisk, Tony Stephens, and Michael Bowers

by John Thompson •

Australian Dictionary of Biography: Supplement, 1580–1980 by Christopher Cunneen

by Paul Brunton •

Crime Fiction by Stephen Knight & The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction edited by Martin Priestman

by Rick Thompson •

Virtual Nation: The internet in Australia edited by Gerard Goggin

by Joel Deane •

Well May We Say edited by Sally Warhaft & Speaking for Australia by Rod Kemp and Marion Stanton

by James Curran •

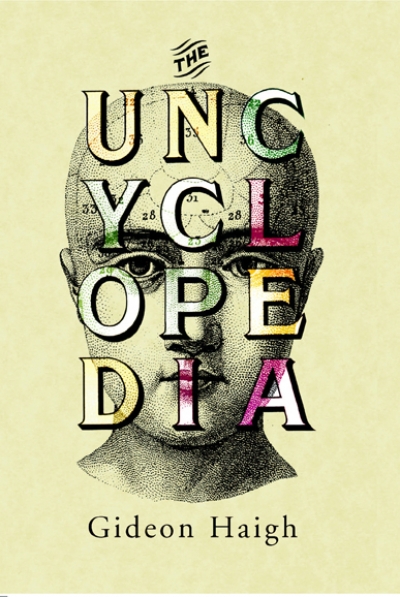

The Uncyclopedia by Gideon Haigh & Names From Here and Far by William T. S. Noble

by Fred Ludowyk •