Sarah Thomas

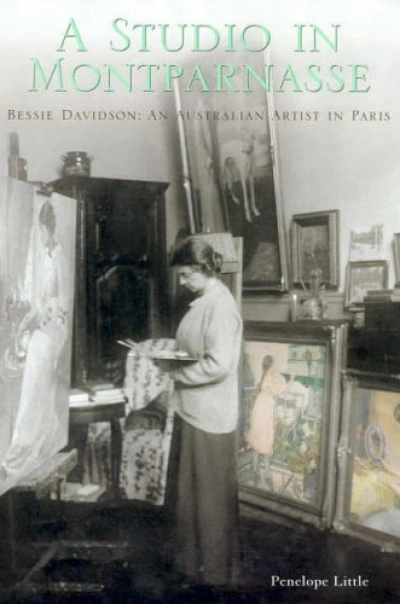

A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson, an Australian artist in Paris by Penelope Little

by Sarah Thomas •

Encounters with Australian Modern Art by Christopher Heathcote, Patrick McCaughey and Sarah Thomas

by Daniel Thomas •

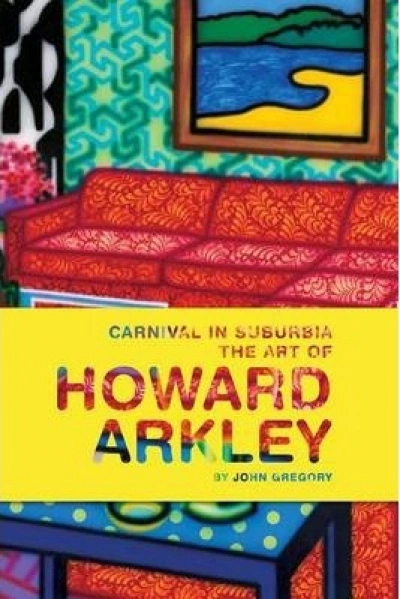

Carnival in Suburbua: The art of Howard Arkley by John Gregory

by Sarah Thomas •

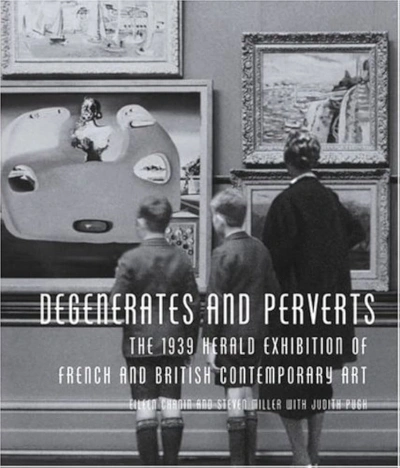

Degenerates and Perverts: The 1939 herald exhibition of French and British contemporary art by Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller (with Judith Pugh)

by Sarah Thomas •