Archive

Making Women Count: A history of the women’s electoral lobby in Australia by Marian Sawer

by Kate Goldsworthy •

Comic Commentators: Contemporary political cartooning in Australia edited by Robert Phiddian and Haydon Manning

by Iain Topliss •

The Age Of Wonder: How the romantic generation discovered the beauty and terror of science by Richard Holmes

by John Hay •

Telling a Hawk from a Handsaw by Chris Wallace-Crabbe

by Gregory Kratzmann •

The Best Australian Stories 2008 edited by Delia Falconer

by Jeffrey Poacher •

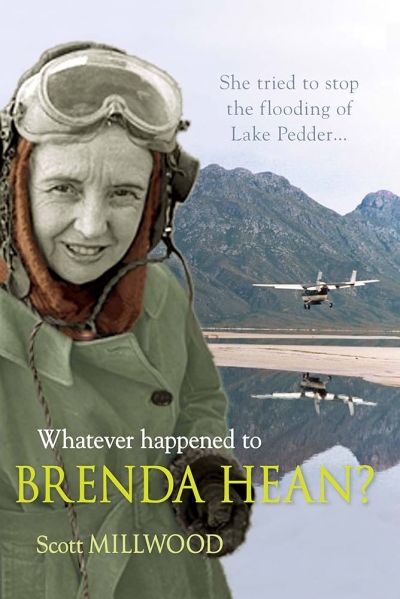

Whatever Happened To Brenda Hean? by Scott Millwood

by Jay Daniel Thompson •

Arts Of Publication: Scholarly publishing in Australia and beyond edited by Lucy Neave, James Connor and Amanda Crawford

by Jay Daniel Thompson •