Ginninderra Press

A Love Affair with Australian Literature: The story of Tom Inglis Moore by Pacita Alexander and Elizabeth Perkins

by Anthony J Hassall •

Unfinished Journey: Collected Poems 1932-2004 by Michael Thwaites

by Philip Harvey •

Leavetaking by Joy Hooton & Temple of the Grail by Adriana Koulias

by Gillian Dooley •

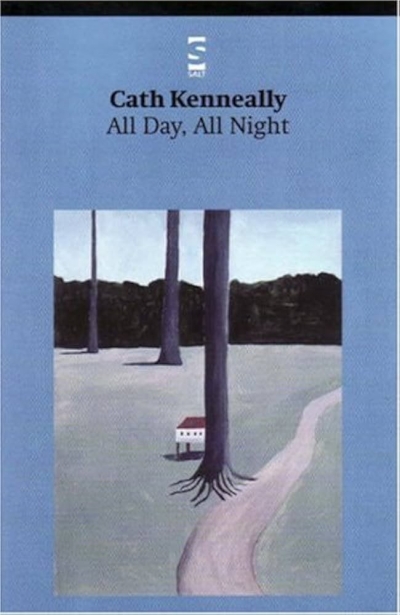

A Cold Touch by Lawrence Bourke & All Day, All Night by Cath Kenneally

by Richard King •