Ashgate

Of Marriage, Violence and Sorcery: The quest for power in Northern Queensland by David McKnight

by Inga Clendinnen •

Dickens and Empire: Discourses of class, race and colonialism in the works of Charles Dickens by Grace Moore

by Graham Tulloch •

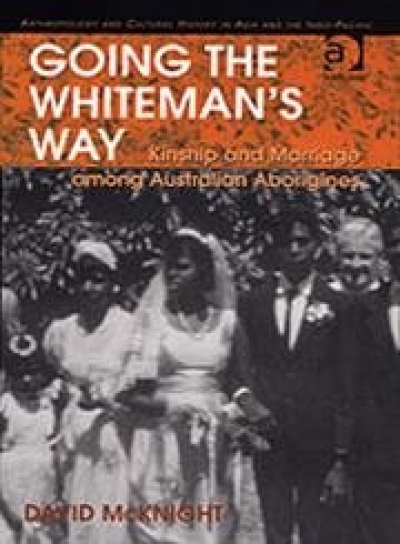

Going The Whiteman’s Way: Kinship And Marriage Among Australian Aborigines by David McKnight

by Inga Clendinnen •

The Third Try by Alison Broinowski and James Wilkinson & Australian and US Military Cooperation by Christopher Hubbard

by Daniel Flitton •