Archive

Living in a New Country: History, travelling and language by Paul Carter

by Gerald Murnane •

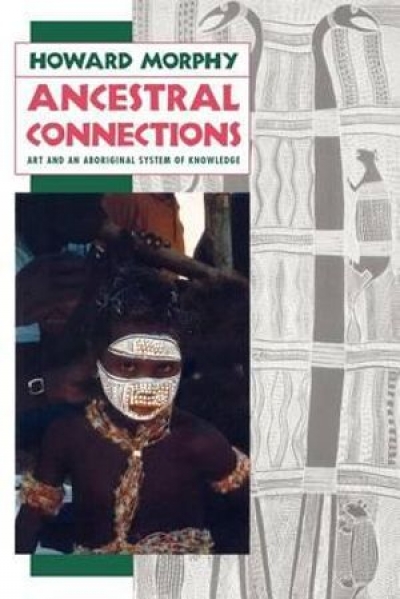

Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal system of knowledge by Howard Morphy

by Tim Rowse •

Why do we read what we read? Bookshelves groan with biography, travel, social theory far left corner, cultural studies creeping up the front, Baudrillard in the back door and out the front. Some people’s books get featured in the weekend papers, others go straight into the back of the car and the second-hand shops. Love, sweat and tears … what’s it all for?

... (read more)Suffrage to Sufferance: 100 years of women in politics by Janine Haines

by Joan Kirner •

Boundary Conditions: The poetry of Gwen Harwood by Jennifer Strauss

by Alison Hoddinott •

What is the relationship between our literary culture and the academy? Moreover, should there be any relationship between the two, or is it healthier if each remains separate, largely isolated from the other? These-questions were brought into focus for me by ‘Word Games’, a provocative essay in the Spring issue of Island, that lively Tasmanian literary magazine.

... (read more)