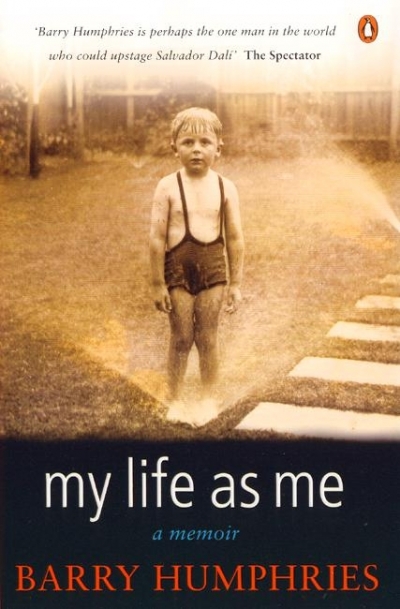

Barry Humphries

‘I invented a character called Barry Humphries,’ the program promised. Beyond his characters, he said, the real man had always lurked behind a mask in various interviews. ‘Tonight you’ll see me.’ And there he was, in mauve jacket and polka dot tie, his features sharp, the voice crisper than ever ...

... (read more)One Man Show: The Stages of Barry Humphries by Anne Pender

300 and all that!

Next month marks the 300th issue of ABR. We’re feeling very generous as we approach this milestone. We invite current subscribers to give away a free six-month subscription to ABR when they renew. This is your chance to introduce a friend or colleague to ABR (recipients of these gifts must not be current or recently lapsed subscribers). All you have to do is to complete the cover sheet accompanying the March issue or contact the Office Manager on (03) 9429 6700 or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. Any current subscriber can take up this special offer if they renew now: your subscription doesn’t have to lapse this month for you to be eligible.

... (read more)The World of Thea Proctor by Barry Humphries, Andrew Sayers, and Sarah Engledow

Once an Australian: Journeys with Barry Humphries, Clive James, Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes edited by Ian Britain

Publishers are like invisible ink. Their imprint is in the mysterious appearance of books on shelves. This explains their obsession with crime novels.

To some authors they appear as good fairies, to others the Brothers Grimm. Publishers can be blamed for pages that fall out (Look ma, a self-exploding paperback!), for a book’s non-appearance at a country town called Ulmere. For appearing too early or too late for review. For a book being reviewed badly, and thus its non-appearance – in shops, newspapers and prized shortlistings.

As an author, it’s good therapy to blame someone and there’s nothing more cleansing than to blame a publisher. I know, because I’ve done it myself. A literary absolution feels good the whole day through.

... (read more)