Archive

Helen Daniel, the editor of Australian Book Review since 1995, died suddenly on Monday, 16 October 2000. Her death has sent waves of shock and sorrow throughout the Australian literary world. According to Andrew Riemer, at the Writers’ Week in Brisbane, held on the weekend after Helen’s death, session after session paid homage to this woman who, without vanity or arrogation, had made her name synonymous with the profession and apprehension of Australian literature.

Her death diminishes all of us. It’s strange to reflect that Helen, who occupied her position so quietly (at times so stoically) was in fact far and away the greatest champion for Australian writing in her generation and that her time as a critic and editor coincided with the great efflorescence of Australian publishing that we now wonder at and ponder.

... (read more)‘We’ve given Ayers Rock back to the Aborigines!’ Perhaps I remember those words so clearly because a friend spoke them to me over the telephone when I was in England, surprised almost daily at the reforms of the Whitlam government and at the international interest they excited. Years later I reflected on the meaning of that ‘we’. Had he said the same words to an English person, the meaning of it would have been different. Addressed to me, that ‘we’ wasn’t so much a classification that included or excluded me: it was an invitation to be part of a community whose identity was partly formed by its relation to Australia and its past and by its preparedness to accept responsibilities for what head been done to the Aborigines – at that time (before we knew about the stolen children), the taking of their lands and desecration of their sacred places. Had I thought about it, that would partly have answered the question I did ask him. ‘What does giving it back mean?’ He couldn’t say. In fact no one I asked could. No one was interested. Everyone was heartened by the generosity expressed in the gesture and enthusiastic in their hopes for a new era.

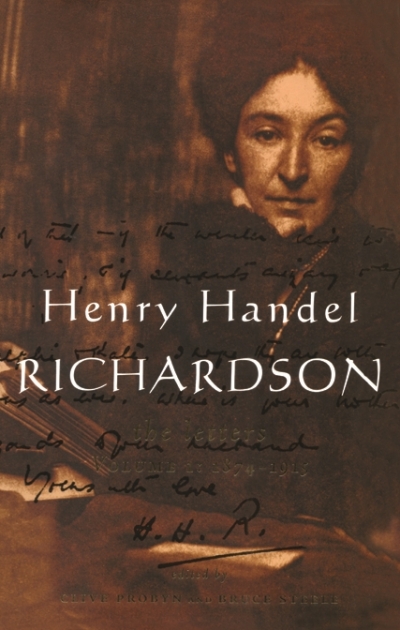

... (read more)Henry Handel Richardson: The letters edited by Clive Probyn and Bruce Steele

It’s usually said that Australians are uninterested in the metaphysical. Where in America the lines between the secular and religious are notoriously blurred, not least in their politicians or sporting heroes invoking God on almost every conceivable occasion, Australians by contrast are held to be a godless lot, their mythologies entirely secular in form and meaning. God is rarely publicly invoked, except by ministers of religion whose particular business it is duly to do so.

... (read more)